REVIEWS

Aida, Copenhagen, January 2005

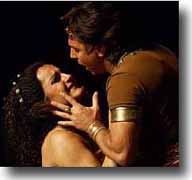

Photo of Roberto Alagna & Gitta-Maria Sjöberg by Søren Bidstrup

Aida in a sleek Danish setting, Financial Times, 31 January 2005

Alagna, prince du Danemark, ConcertoNet, February 1, 2005 [external link]

_______________________________________________________________

'Aida in a sleek Danish setting

Richard Fairman, Financial Times, 31 January 2005

Seen at night, the warmly lit interior of Copenhagen's new opera house glows invitingly across the water. The building is situated in a uniquely privileged position, opposite the Amalienborg Palace, lining up on an axis with the proudly domed Frederikskirken - so close to the city's heart that arias could easily waft over the water on an evening breeze.

Getting to it, however, is another matter. Although it looks so near, the building is a good 15 minutes by road from the centre. Plans are in train for a big redevelopment of this city-centre wilderness, but for the moment it is pretty bleak. Drive out of the centre to the south-east, past a sign to the golf range, take the next on the left and head out into a no-man's-land until the lights of the huge hulk of the opera house beckon in the distance. Or just hope that the taxi driver knows the way.

He should do. The opera house, known as Operaen, has become something of a national obsession in the past few months prior to its opening, as one controversy after another has rained down on its huge cantilevered floating roof. This has not been because of any charges of government waste. Operaen has been given to the Danish nation, the gift of one man, Maersk McKinney Moller, through the A.P. Moller and Chastine McKinney Moller Foundation. And at a cost of approximately 2.5bn Danish Kroner (£232m) it is not a gift that has been made on the cheap.

Now aged 91 and reputedly the wealthiest person in Denmark, Moller is a determinedly private man. He has resisted almost all calls for interviews despite the media blitz, surfacing only once on television to reassert his personal interest in the opera house project. The building does not bear his name - contrast how the name of Alberto Vilar, another substantial private donor to opera, proliferated around the world in the 1990s - and the standing bronze plaque to the Foundation in the foyer is a modest affair, even if rather a lot of people may find themselves tripping over it.

The controversy has come over Moller's determination to get his own views heard and acted upon. He chose an architect, Henning Larsen, with whom he had collaborated successfully in the past, but as the opera house has neared completion, reports have suggested that the two big egos have fallen out. A disagreement over whether the glass front of the building should have supporting metal bars was just one of the factors that led to Larsen's denouncing the final result as a "compromise that failed" last week.

Where it is, how it looks, how much it cost, the way it was planned and constructed - almost every aspect of Operaen has come under fire. But now that the opera house is up and running, will anybody care? At the first opera performance on Wednesday, it seemed the epitome of a practical, modern public building. Its "look" is at once handsome and plain in the Scandinavian style. The foyers are spacious. The views across the water are a constant delight. There are enough toilets - and no, that is not a minor concern, as anybody who has queued in vain at the budget-busting Opéra Bastille in Paris will know.

Inside the auditorium one hardly even notices the ceiling, adorned with its 105,000 sheets of 24-carat gold leaf and criticised as "megalomaniac and vulgar" by one Danish architectural writer, while the dark maple wood walls are distinctive and comforting. Overall, the effect is sleek, clean, impressive in its sense of height and space, though with a seating capacity of only about 1,500 it is important to remember that this is not a big house - closer in size to Glyndebourne than Covent Garden, let alone the Met in New York.

For all that, it is a step up from its much-loved predecessor, the Old Stage at the Royal Danish Theatre, where opera spectaculars were of necessity thin on the ground. So what better work to open Operaen on Wednesday night than Verdi's Egyptian epic, Aida, in a production that seemed to have been given a budget worthy of the Pharaohs? Doubtless knowing the preferences of a typical opening night audience, the producer Mikael Melbye delivered an old-fashioned, cruise-down-the-Nile spectacular. There were enough silly, camp costumes here for a Hollywood blockbuster on the Moses story or - more likely - Carry On Around the Pyramids.

For genuine opera-goers there was also the chance to catch Roberto Alagna, the leading French tenor, in his first attempt at Radames, the heaviest role he has essayed to date. Alagna is not by nature one of opera's heroic tenors, but he delivered a judicious balance between sensitive lyricism and those ringing top notes that he likes to hang on to forever. How brave, too, to bare so much flesh in his mini tunic; the tan looked great, too, but he might have left some in the bottle for the rest of the cast. The chorus looked like Eskimos on a summer safari.

Alagna was well partnered by Randi Stene's unusually deeply felt and interesting Amneris, though she does not really have the low notes for the part. Otherwise, Stephen Milling's sonorous King was the vocal highlight of a rather mixed cast, which included Gitta-Maria Sjöberg as an able Aida, John Lundgren's forceful Amonasro and Christian Christansen as a Ramfis on the gruff side. It may be that the sets were playing tricks, but the projection of the voices sometimes sounded strange, almost as if they were in an echo chamber at the back of the stage. Not so the orchestra, which played well for conductor Manfred Honeck. Although he is no Italian in matters of style, he didn't half let rip in the final act, as Melbye wowed the audience with his temples flying in left and right, above and below.

Although less crowd-pleasing, the rest of this opening season at Operaen looks appropriately ambitious. Kasper Bech Holten, the Royal Danish Opera's young artistic director, has secured an extra 19m (£13m) a year to run the new theatre, while keeping the old one in use for Baroque and classical operas, as Paris does with the Opéra Bastille and the Palais Garnier. His own production of Wagner's Ring cycle is heading for completion and there will be an important premiere in March, when Danish composer Poul Ruders tries to match the success of his first opera, The Handmaid's Tale, with his new Kafka's Trial. By then anybody with an interest in opera will surely know the road to Operaen.

This page was last updated on: February 2, 2005