Tiefland Further Reading

Table of Contents

Biographical notes: Eugen D'Albert by Ian Lace

Biographical notes: Àngel Guimerà from L'Associació d'Escriptors en Llengua Catalana

Plot and musical analysis by George P. Upton

Detailed synopsis by Leo Melitz

Review of the Marton/Kollo recording of Tiefland by Ian Lace

by Robert von Dassanowsky

Catalan Landscape circa 1900

Biographical notes: Eugen D'Albert

Ian Lace, Music on the Web (UK), 1999

Eugen D'Albert was born in Glasgow in 1864. He bore a French name of

Italian origin, was German by adoption and died a Swiss citizen in 1932

in Riga! His parents moved south to Newcastle when he was very young and

he was drilled as a public pianist at a very early age. He hated England

and after several years in London made his way to Vienna at the age of

17. He composed 22 operas taking in every "problem" story ever tackled

in opera from Wagner to Krenek's "Johnny spiel auf". Tiefland (1903), in

the Italian 'verismo' style, shows influences of Wagner and Richard

Strauss and there is much use of Viennese waltz forms. D'Albert's

orchestration is sumptuous. It is set in Spain; partly on an isolated

mountain slope in the Pyrenees and partly in a lowland valley in

Catalonia. D'Albert always keen to soak up local colour and atmosphere,

went on a walking tour of the region and had a musical scholar obtain

Spanish dance tunes and shepherd's calls for him. For D'Albert,

authenticity was an integral part of naturalism.

Biographical notes: Àngel Guimerà

L'Associació d'Escriptors en Llengua Catalana

Àngel Guimerà (Santa Cruz de Tenerife, 1845 - Barcelona, 1924) was a

playwright and poet, the only 19th century Catalan playwright to be

performed elsewhere in Europe. He began his literary career as a poet,

was declared "Mestre en Gai Saber" (Master in the Art of Poetry) in 1887

and presided over the 1889 Jocs Florals (Literary Contest) in Barcelona.

His first tragedy in verse "Gala Placídia" (1879) is situated within the

romantic-historic tradition. With his "Mar i cel" (Sea and Sky) of 1888,

he had an unprecedented success, the work being translated into eight

languages which brought the author into the international arena. This

work was the beginning of his most productive period which would last

until 1900, a period in which most of his representative works were

staged: "Maria Rosa" (1894) and "Terra baixa" (The Lowlands) in 1897,

along with "La filla del mar" (Daughter of the Sea) (1900) which were

brought more than once to the cinema screens. These works portray, with

realistic touches, life in Catalonia at the time. He was elected

President of the Lliga de Catalunya and his political speeches made all

over Catalonia are collected in the volume "Cants a la patria" (Hymns to

the Nation) of 1906. In 1909 he was given a multitudinous popular

homage. He was an early member of the Institut d'Estudis Catalans

(1911).

Guimerà's study

Plot and musical analysis of Tiefland

George P. Upton, The Standard Operas Their Plots and Their Music, 1928

(new edition, enlarged and revised by Felix Borowski)

"TIEFLAND" is a musical setting of a well-known and popular Spanish

drama, originally written in Catalonian by Angel Guimera, and called

"Tevva Baixa." The Spanish dramatist, José Echegaray, next produced, a

version of it, called "Tierra Baja." An English version has been made

familiar to American audiences by the actress, Bertha Kalich, as "Marta

of the Lowlands." The libretto of "Tiefland" was adapted from the

Catalonian version by Rudolph Lothar.

The opera was first produced in Prague in November 1903, but without

marked success. It was then revised by D'Albert and brought out in

Hamburg in 1907, also in Berlin, and had a long run in both cities. Its

first performance in this country took place in New York, November 23,

1908.

The opera is divided into a prologue and three acts. The prologue opens

among the Pyrenees Mountains and discloses the shepherd Pedro tending

his flocks. He lives in solitude but has dreamed that the Lord will

sometime send him a wife. The rich landowner Sebastiano appears and

informs Pedro that he has brought the young girl Marta to him for his

wife, and that he must leave the mountains and go down to the Lowlands

for his wedding. Pedro, thinking his dream is realized, is overjoyed at

the prospect, although Marta is unwilling and will not even look at

Pedro. Behind Sebastiano's apparently generous proposal, however, is a

dark plot. Years before this, Marta, the daughter of a strolling player,

had come to the Lowlands where Sebastiano dwelt and had been induced to

live with him as his mistress in consideration of his gift of a mill to

her father. As Sebastiano is now about to wed an heiress, he has plotted

to marry Marta to Pedro, and at the same time continue his illicit

relations with her.

The first act is devoted to Pedro's arrival at the Lowland village,

where his marriage is to take place at the mill. At first he is unable

to understand why the villagers, who are aware of Marta's relations to

Sebastiano, make sport of him. After the wedding, Marta, wishing to

avoid Sebastiano, does not go to her chamber nor accompany Pedro, all of

which mystifies him still more.

In the second act Marta begins to love her husband, but Pedro's

persecutions continue and at last he tells her he is going back to the

hills. She begs to go with him and tells him her story, whereupon he

advances with his knife as if to kill her, but his love is stronger than

his rage and they decide to go together. At this moment Sebastiano

enters, ejects Pedro, and makes advances to Marta.

In the last act the heiress whom Sebastiano expects to marry rejects him

and he renews his advances to Marta, who calls to Pedro for help. He

rushes in with his knife, but, seeing that Sebastiano is unarmed, throws

it down and strangles him. Catching Marta in his arms, he rushes out

with the passionate exclamation, "Back to the mountains, far from the

lowlands, to sunshine, freedom, and light."

It will be seen from this brief sketch that the plot is of the simplest

kind and the story merely one of elemental human passion, ending in the

inevitable tragedy. It is of the same type as the subjects chosen by the

writers of many modern Italian operas, for instance Mascagni in

"Cavalleria Rusticana" and "Iris," Puccini in "Tosca," and Leoncavallo

in "Pagliacci"; in a word, it is the jealousy and sudden passionate fury

of the South, but set forth in this opera in the regular and symphonic

Teutonic manner, so that its outcome is somewhat incongruous. It

resembles these modern Italian music-dramas, however, in that it

contains no formal numbers or sustained melodies. The composer has

sought to make his music grow out of the dramatic situation, with the

'result that it is declamatory rather than lyrical, and yet there are

strong and beautiful moments, such as Pedro's recital of the vision of

the Virgin; the shepherd's description of his killing of the wolf; and

Marta's story as she sits by the fire; as well as the passionate climax,

when after the tragedy they leave Tiefland and go back to the mountains.

But upon the whole, like "Pagliacci" and "Cavalleria Rusticana," the

interest of this opera is dramatic rather than musical. The "Marta of

the Lowlands," as presented by Kalich, however, is much stronger

dramatically than the "Tiefland" of D'Albert.

Vilhelm Herold, the great Danish tenor, who interpreted the role of Pedro in the early 20th century

Detailed synopsis of Tiefland

By Leo Melitz, The Opera Goer's Complete Guide, 1921

(Translated by Richard Salinger, revised and brought up to date after

consultation with the Librarian of the Metropolitan Opera Company

by Louise Wallace Hackney),

TIEFLAND

Music drama, in three acts and a prologue, adapted from the work of

Guimera by Lothar. Music by Eugen d'Albert.

CAST: Sebastiano, a rich landowner. Tommaso, an old man. Moruccio,

Martha, Pepa, Antonia, Rosalie, Nuri, Pedro, Nando, all in the service

of Sebastiano. A priest. Place, the Pyrenees and the valley of

Catalonia. First production, Prague, 1903.

PROLOGUE: A rocky fastness in the Pyrenees. The shepherd Pedro, as long

as he can remember, has lived among the hills, which be loves. (Pedro:

"Wonderful 'tis to me.") He seldom sees any one except his

fellow-shepherd, Nando, and women almost not at all, but he dreams that

the Mother of God will some day send him a wife. (Pedro: "Nay, de not

laugh, I mean it.") He is satisfied with his free life (Pedro: "Glorious

'tis to me") and thankfully repeats the Paternoster. His employer, the

rich Sebastiano, has forced the beautiful Martha to accede to his

desires, installing her as manager of the mill. He now wishes her to

marry (Sebastiano: "Have no fear") and to take Pedro for her husband. He

has brought her to the hills with this end in view, trusting to Pedro's

ignorant simplicity and obedience for the rest. Pedro, of course, thinks

the long-wished-for wife has been sent to him, and willingly consents to

go to the Lowlands and live with Martha in the mill. Martha is less

willing and will not look at Pedro. She departs with Sebastiano, and

Pedro tells Nando of his good fortune. (Pedro: "Joy comes to me!")

ACT I. The interior of the mill. Sebastiano's servants know that he is

Martha's lover, but that their master must make a rich marriage to

maintain his position. They discuss the matter, and little Nuri

innocently tells them of a conversation she has overheard between

Sebastiano and Martha. (Nuri: "If I walk, and walk, and walk"; " 'Twas

eventide.") The maidservants scorn Pedro, who, unaware of the situation,

is betrothed to Martha ("This great fool knows less than nothing"), and

joke broadly with Martha over her coming nuptials. She drives them away,

bitterly complaining of her loneliness. (Martha: "No one have I to help

me in my need.") Nuri tries to make her smile, but her innocent

questions only hurt, and Martha sends her away. (Martha: "His, body and

soul.") Moruccio tells old Tommaso the real state of affairs, and they

quarrel. The villagers are hilarious over the deception of Pedro.

(Pedro; "I thank you all.") The marriage takes place, and it is

Sebastiano's intention to return at night and visit Martha as usual.

(Sebastiano: "Martha, you know.") She, wishing to avoid him, does not

enter her chamber, nor does she ac-company Pedro, although she is now

convinced that the simple shepherd has acted in good faith and knows

nothing of her relations with Sebastiano. (Pedro: "You mean that I have

earned this without working.") Poor Pedro is puzzled by her strange

conduct and tears, and knows not what to do. (Pedro: "Now what to do I

scarcely know.") A light appears suddenly in Martha's room - Sebastiano'

s signal - which adds to the mystery.

ACT II. Same scene, at dawn. Nuri is heard singing outside. (Nuri: "The

stars are going to sleep.") She enters, knitting industriously, and

tells Pedro she is making him a fine new jersey. He replies that he is

going away. (Pedro: "Yes, far away from Martha.") Martha's love is

turning toward her husband, and she becomes jealous of Nuri, driving her

from the house. Pedro goes with her, and Martha, running after them,

half distraught, meets old Tommaso. She confides in him, explaining that

her old rascal of a stepfather had sold her to Sebastiano. Tommaso

advises her to tell Pedro all. (Tommaso: "Every one laughs, and Pedro

knows not why"; Martha: "Think of your own dear daughter.") She feels

that Pedro really loves her. (Martha: "Let him despise me, then! He

loves me.") The old man leaves her with his blessing. (Tommaso: "In God'

s strong arms I leave you.") The chattering women drive Pedro to return.

He shakes one of them in exasperation, then entering the house, tells

Martha he must go back to his solitude in the hills. She asks him to

take her with him, and he answers her with bitterness. (Martha: "Ah!

thou art right. With my beloved.") She laughs hysterically, and Pedro

advances with a knife to kill her. (Martha: "Only a weariness is life to

me!" Pedro: "I sought to kill the woman whom I love!") He suffers

remorse, and they determine to fly together. (Duet: "There shall we go,

high up in the hills!") They are intercepted by the villagers, who enter

with Sebastiano to congratulate them. Sebastiano, with effrontery,

thrums on a guitar for Martha to dance as of old. (Sebastiano: "Wind

round your form the seductive mantilla.") He strikes Pedro, who rushes

at him furiously, but is overpowered by the villagers and dragged away.

ACT III. The same scene. The news of Sebastiano's conduct has caused the

rich heiress to reject him. With increasing passion he desires Martha,

but she loves Pedro. (Sebastiano: "Little sweetheart, you are mad.") He

defies God. ("Heaven has no ears for you.") Martha scornfully refuses to

listen to him. ("No longer am I weak and helpless.") She calls to Pedro.

He has escaped and bounds into the room like some savage animal, drawing

a knife. ("Sneak away, wouldst thou, coward dog!") Seeing Sebastiano is

unarmed, he throws down his weapon and they fight with their bare hands.

Sebastiano tries to pick up the knife. Pedro puts his foot on it, and

flies at his enemy's throat. Silently they wrestle, until Pedro throws

Sebastiano aside as if he were a rat and calls the people in to witness

his work. Scornfully he asks them, as they stand dumb with amazement,

why they do not laugh now. (Pedro: "Well, good friends, why don't you

laugh?") Then, bearing Martha in his strong young arms, he escapes with

her to freedom among the mountains. (Pedro: "Far up, far up in the

mountains! To sunshine and freedom and light.")

Maria Calllas as Marta Athens 1945

Recording Review

Ian Lace, Music on the Web (UK), 1999

Eugen D'ALBERT Tiefland Eva Marton; René Kollo; Bernd Weikl; Kurt

Moll. Münchner Rundfunkorchester conducted by Marek Janowski

ARTS 2CD 47501-2 (134:46)

[...] The drawback with this 2 CD set is that although there is a

substantial enough booklet with good notes in English, French and

German, the libretto is only in German so unless the listener is fluent

in that language, it is impossible to appreciate all of D'Albert's

subtleties and nuances. Briefly, the story concerns a rather naive and

lonely young shepherd, Pedro who is persuaded by landowner, Sebastiano

to descend from his mountain home to the plains below and to marry the

lovely Marta.

Marta is Sebastiano's young ward and mistress. Sebastiano has an

ulterior motive because he wants to make a good profitable marriage to

bolster his dwindling assets - but he also wants to keep Marta as his

mistress. At first Marta is repulsed by the guileless Pedro who she

thinks is a rogue but when she realises that he is innocent and really

loves her, she falls in love with him when she discovers Sebastiano's

deception. Pedro and Marta confront Sebastiano with their love but he

will not let Marta go particularly as he knows that he has now lost

everything because his intended bride has also been told of his

duplicity. In the ensuing fight between Pedro and Sebastiano, Sebastiano

is killed and Pedro and Marta flee for the purer atmosphere of the

mountains.

The cast is impressive in this 1983 recording. René Kollo is as

magnificent as he was as Walther in the 1971 Karajan recording of the

Die Meistersinger as he ranges from incredulous innocent, to ardent

lover, to vicious avenger. Bernd Weikl is also excellent as Sebastiano,

the scheming villain with a heart. Eva Marton also impresses as Marta

but curiously the important role of Nuri is not credited in the

booklet's cast list (although more minor characters are!). The best

material is given to the men. Highlights include: the evocative

orchestral opening vividly portraying life in the high mountains; the

Act I scene when the village maidens make fun of what they perceive as

the boorish naivety of Pedro and Marta's anxiety about being separated

from Sebastiano against lively Richard Strauss/Viennese-like material

followed by Sebastiano's Ochs-like reassuring serenading of Marta to

similar material found in Der Rosenkavalier but with more passion and

irony (the orchestral accompaniment at the end of this scene is

positively ravishing). Act II highlights include Pedro's big aria the

wolf song in which he tells Marta of the wolf he had killed on the

mountains to protect his sheep (serving as an allegory for the situation

between Marta, Sebastiano [the human wolf] and himself); this is

followed by the glorious love duet between Marta and Pedro as Marta

realises the truth of the situation.

Janowski leads his his choir, orchestra and soloists in a passionate and

moving performance of this much negelected opera - little wonder that it

had such an effect on Korngold! At such a bargain price this is an

operatic set that everyone who loves full blooded late Romantic music

should snap up without hesitation.

Rene Kollo, Pedro in

the 1983 recording

'Leni Riefenstahl's self-reflection and romantic transcendence

of Nazism in Tiefland'

By Robert von Dassanowsky, Camera Obscura 35, 1995/96

[...] Tiefland offers not only the filmmaker's examination of her own

culpability vis-à-vis Nazism but expresses a pre-feminist consciousness

that places her acceptance of fascist militarism and male dominance in

Triumph des Willens in a new and revealing perspective.

Even as Riefenstahl's promotion of Hitler in Triumph generates a palette

of fascist imagery, her Romanticism, like her appreciation of the body

cult cannot be used to reduce her entire output to an example of a

specific fascist aesthetic. Essentially a Bergfilm (mountain film) maker

and a nature-mystic, Riefenstahl gave Hitler's set pieces the needed

emotional association with German tradition and culture. As B. Ruby

Rich, who finds German Romantic painting influential in Triumph,

understands: "the principles of Romanticism [were] subjugated to the

Nazi ideology by means of specifically Romantic pictorial devices." The

concept of the nature-bound outsider as prophet, so prevalent in

Riefenstahl's work, is also to be found throughout the German Romantic

literary canon, in the works of Novalis, Tieck, Goethe, von Eichendorff,

and Hölderlin, where it is anything but reactionary or authoritarian.

Furthermore, Eric Rentschler has shown that the celebration of mountain

purity in Arnold Fanck's Alpine epics of the 1920s and 1930s, and in Das

blaue Licht, does not after all, aim to provide "proto-Nazi sentiments"

of "Führer-worship." The Romantic Bergfilm genre has been reworked and

adapted in popular German cinema from its birth in the early Weimar

Republic through the West-German Heimatfilm (homeland film). Renschler

also believes that Das blaue Licht "crosses borders and defies fixities"

in its ideological and technical adaptation of the Bergfilm. I feel that

Tiefland, in turn, should be seen to cross and defy the filmmaker's

previous concepts and conventions, most importantly in the use of her

established Romantic vocabulary to subvert and counter a paradigmatic

authoritarian order.

Despite their similar function as erotic stimulus to the male

characters, the social outsiders portrayed by Riefenstahl in Das blaue

Licht and Tiefland are distinctly different from each other. The

mountain girl Junta in Licht is destroyed by the materialism of the

villagers and is a male fantasy image, a martyr, a "mythical essence."

Her mimosa-like nature, her aesthetic-spiritual understanding of the

blue crystals, and her final transformation into an icon, denotes a

vague messianic image. The character of Martha in Tiefland is first a

very human opportunist with no lofty qualities or notions. Her eventual

desire to help those oppressed by her "Führer" speaks of sympathy and

humanism not martyrdom or utopianism. Similarly, Tiefland's concept of

transcendence is a simplistic and personal one, not the occult manifesto

of Das blaue Licht. Indeed, Renata Berg-Pan finds Tiefland to be weak

because "Riefenstahl no longer had the same relationship to the topic

which had compelled her to take it up in 1934. She had outgrown the

emotional bonds attaching her to the theme." In his 1972 BBC interview

with Riefenstahl, Keith Dewhurst dispels Riefenstahl's early mysticism

with Tiefland, marking it as "the first time in one of her films [that]

she tells a story with a social message-poor peasants against a rich

landlord." What Riefenstahl presents of herself and, her art in Hitler's

Germany via Tiefland ultimately makes it as important as any film of her

career. [...]

[...] Although Sanders-Brahms believes that Riefenstahl understood the

opera to echo her own situation, she does not mention that Riefenstahl

increased the self-reflexive quality of the film by altering the

original opera plot to preseat Martha as succumbing willingly to

seduction by the evil Marquez. Nor does she detail Martha's opportunism

in order to become an admired and respected lady. Berg-Pan originally

sets up the basis for such autobiographical analysis but does not pursue

this line of inquiry. She is convinced that the scene in which the

Marquez (Bernhard Minetti) enters the inn to witness Martha's dancing

has fascist overtones: "the master Don Sebastian peremptorily stomps

into the inn, is immediately greeted by the peasants with bowed heads

and other forms of self-humiliation, and as the master, is welcomed by a

woman who can entertain him. He has the power to take her, and she

submits without question." In presenting Martha and her dance to the

observant Marquez, director Riefenstahl assumes the mate gaze to

objectify and eroticize her own image, prompting one male critic to

comment on the film's "undulating bosoms." But the gaze is from the

point of view of the boorish male peasants who paw her and of the

Marquez Don Sebastian, the powerful, abusive leader. Despite

Riefenstahl's awareness of her own photogenic beauty, she would be, by

the filming of Tiefland, more conscious of the subservient female role

in Nazi society and her own problems as female artist in Nazi political

circles than earlier in her career. Oppressive male dominance is one of

the guiding themes of the film, therefore Riefenstahl must connect the

traditional male figures with an objectifying male gaze. She later

subverts this gaze by the actions of Martha and with the non-traditional

male figure of Pedro. [...]

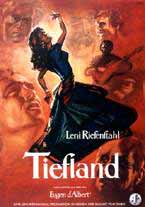

Contemporary poster for the Leni Riefenstahl film version of Tiefland

Sources & Bibliography

Biographical notes: Eugen D'Albert

Review of the Marton/Kollo recording

www.musicweb.force9.co.uk/music/classrev/Apr99/tiefland.htm

Biographical notes: Àngel Guimerà

www.escriptors.com/

Tiefland plot and musical analysis by George P. Upton

www.intac.com/~rfrone/operas/Books/Upton_Standard/Albert.htm

Detailed synopsis of Tiefland by Leo Melitz

www.intac.com/~rfrone/operas/Books/Melitz_Complete/

'Leni Riefenstahl's self-reflection and romantic transcendence

of Nazism in Tiefland' by Robert von Dassanowsky

www.powernet.net/~hflippo/cinema/tiefland.html

Texts of Guimerà's poetry (in Catalan)

www.mallorcaweb.com/Mag-Teatre/poemes-solts/guimera.html

www.xtec.es/~evicioso/bcnes/guitibid.htm

Detailed biography and literary essay on Guimerà (in Catalan)

www.uoc.es/lletra/noms/aguimera/index.html

Complete German libretto of Tiefland

www.impresario.ch/libretto/libdaltie.htm

The Prague State Opera House where Tiefland premiered in 1903

This page was last updated on: September 9, 2003