This page was last updated on: August 1, 2006

ARTICLES & INTERVIEWS

May - July 2006

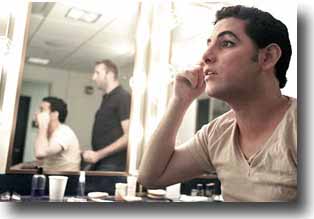

Juan Diego Flórez backstage at the Washington National Opera, May 2006

Photo © Karin Cooper

Peru's Peak Performer, The Washington Post, 14 May 2006

For tenor, bel canto comes naturally, The Baltimore Sun, 15 May 2006

"Ich wollte Rocksänger werden ...", Die Welt am Sonntag, 2 July 2006

Sentimiento over you, The Times, 22 July 2006

Flórez confiesa que siempre le gustaron los Rolling Stones, EFE, 20 July 2006

______________________________________________________________

Peru's Peak Performer

Daniel Ginsberg, The Washington Post, 14 May 2006

At 33, Juan Diego Flórez Is at the Summit of Bel Canto Singing

This weekend, tenor Juan Diego Flórez is to make his debut with the Washington National Opera. The 33-year-old singer fills the role of Lindoro in Gioacchino Rossini's "L'Italiana in Algeri" ("The Italian Girl in Algiers"), a comic opera about the escape of a loving couple from the clutches of an iron-fisted if benighted dictator. Flórez is part of a cast that includes the Russian husband-wife duo of Olga Borodina as the heroine Isabella and Ildar Abdrazakov as Mustafa, the dictator. Since his much-heralded breakthrough performances in Italy a decade ago, Flórez has become one of the most sought-after bel canto singers in the world, highly regarded for his sweetly focused, quicksilver voice. Though now residing in Italy, the singer maintains close ties with Peru, where he was born and began his early musical studies. Decca recently released his third album, "Sentimiento Latino," a collection of Peruvian and Latin American popular songs, and the country also issued a national stamp in his honor.

Last Monday during rehearsals at the Kennedy Center Opera House, the singer sat for a backstage interview with Washington Post contributor Daniel Ginsberg.

Please talk about the role of Lindoro. Is he a very complicated figure? Is Rossini generous to the character musically?

A This is a very generous role singing-wise. He has two great arias. . . . The second aria, "Concedi, concedi amor pietoso," is musically beautiful and very demanding, like the first. . . . Acting-wise, it's not so demanding. He's a simple guy and he doesn't have to do much. . . . It's maybe one of the Rossini operas that have more beautiful and difficult music for the tenor. . . . It's very high and airy -- very light.

How did you come to focus so much on the operas of Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini? What attracts you to the bel canto repertoire?

I think it's my voice. You have a voice that fits a certain repertoire, and my voice fits the bel canto repertoire, especially Rossini.

It's a light, lyric tenor voice that's very agile. It has a lot of flexibility so it can sing all that is demanded from Rossini, especially the coloratura -- the runs -- the high notes, the jumps and very long phrases. And also, it works not only in the virtuoso stuff, but also in the legato and the chiaroscuro, the shading of every phrase.

Do you hope to expand into the more dramatic roles of Verdi or Puccini?

I am happy with what I sing. The goal is to keep that repertoire.

I think you are born with a voice and you keep that voice. You might lose flexibility and that might move you to another repertoire because you cannot sing more high notes and other things that are lost with age. My purpose is to keep the characteristics of my voice that have made me, in a way, important in the world of opera. . . . You achieve that by sticking to your repertoire. You can add other operas, but you have to know that they are good to your voice.

Keeping a good technique helps. I am always trying to be better... I am very perfectionistic and a strong critic of myself. I think that it helps me to be always updated... not only in technique but also in interpretation, in acting... Keeping the voice fresh is very good.

How did your technique emerge? Did everything just click at some point?

In 1994 [while studying at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia] I met Peruvian tenor Ernesto Palacio, who is now my manager. Before, I was always improving, but little by little, very slowly. When I met him, he helped me with my technique. Suddenly, I started to sing much better, to find easier high notes, to find faster runs in Rossini, to have more volume.

Basically, I was singing very round and I had to sing more clear. By singing more clear, I found my high notes. I always had a high C, but not as easy. My whole range became more projected -- it had more volume. It was more clear and had more of an edge. At that point, I would go to a room by myself and work to try to find my voice.

In 1995, I met Marilyn Horne at the Santa Barbara Academy Summer School. She said, "Son, you are ready to do a career. You shouldn't be studying anymore. You should go out and sing." She was so eager to help me, and she went to auditions with me. I always keep in touch with her. She is a great Rossini singer. You learn from her just by listening to her recordings. Her breath control and phrasing are amazing.

What has your success meant for your home country of Peru?

It has meant a lot.

They are very proud. It is a country that has many problems with many poor people.

To have a person who, in a way, puts the name of the country in a high place is a source of pride. For them, it's incredible and they value it so much.

When I go to Peru, everyone recognizes me in the streets. The humble people know me. . . . Next year I will do a benefit concert for the poor, and I plan to do many more of them to help.

Your new album seems to be more of a crossover work. Was it a commercial decision to take that approach or was there something else that attracted you to the project?

I grew up with these songs. My father was a Peruvian-music singer, and many of the songs that I recorded are songs that I sang with my guitar back in Peru. It was so natural and enjoyable for me to make a CD like that.

Also, it's a kind of tradition since Caruso, for all tenors who have careers to record songs from their home countries. Caruso recorded Neapolitan songs. [Jussi] Bjorling and Domingo have recorded so much of that. It's something of the tenor, you know. You expect that -- sooner or later that has to come, especially if that is your heritage.

There seems to be a continual search underway to find the successor to Pavarotti and Domingo. Do you feel that this very open search creates undue burdens on promising artists?

Since 1999, people always ask me, "Are you the next Pavarotti?" Or they say, "You are the fourth tenor. What do you think about that?" Things like that. I say you flatter me because I love Pavarotti, but we have essentially different repertoires. He sings more Verdi and Puccini. I go to Rossini instead of going to Verdi. I was of course honored, but I didn't see much in the way of comparison.

Then Pavarotti said it. They asked him, "Who is your successor?" He said, "Well, I think it's Juan Diego Flórez." It's incredible that Pavarotti says something like that. When you hear these sacred singers -- Pavarotti or Domingo -- say that about you, it's the greatest prize.

For tenor, bel canto comes naturally

Tim Smith, The Baltimore Sun, 15 May 2006

In mid-1830s' Paris, the music world heard a totally unexpected sound from a human voice, which, the story goes, Rossini likened to "the squawk of a capon having its throat cut."

But soon enough, audiences couldn't get enough of that sound, and it still heats up audiences today: The tenor's high C. The money note. Produced not by falsetto, but full-throttle from the chest, a technique first credited to Gilbert Duprez.

Today, no one produces such notes to more public acclaim than Juan Diego Florez.

The Peruvian tenor with the darkly handsome looks of a telenovela star is making his Washington National Opera debut in Rossini's comic, coloratura-powered L'italiana in Algeri (The Italian Girl in Algiers).

"I am thrilled to have Juan Diego Florez in Washington," Placido Domingo, the company's general director and superstar tenor, says in an e-mail from London. "Without any doubt he is the most exciting singer for this very difficult repertoire."

That repertoire, known by the Italian term bel canto (literally, "beautiful singing"), includes the operas of Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini, operas filled with curvy melodies that demand great technical flexibility, and at least for the tenors and sopranos, a lot of stratospheric leaps and bounds - the wiggly world of coloratura.

Although clearly to the bel canto born, Florez' first performances, during his early teens, were actually of Peruvian and other Latin American pop songs - in Lima piano bars.

"That music was always at my house when I was growing up, so it always came natural for me," Florez, 33, says.

His father sang Peruvian popular songs; his mother danced the marinera, Peru's national dance; his grandmother liked to play tangos on the piano.

You get a good idea of what the young Florez was up to from his latest Decca recording, Sentimiento Latino. From a gently flowing Bello durmiente to a sexy account of the familiar Granada, it's irresistible.

"It was fun to do this CD," Florez says. "And it is traditional for tenors to sing something of their own country. Caruso and Gigli did it with Italian songs, even Bjorling [with Swedish songs]."

Florez was not exactly primed for tenordom.

"I knew about opera, but didn't give it much thought," he says. "Toward the end of high school, a teacher of the chorus put on some zarzuelas. He made me the lead and tried to make me sing like a tenor, but I was just imitating what he showed me."

He imitated well enough for the teacher to start giving Florez private lessons. "My voice became, in a way, much more manly in those lessons," Florez says. "But I took them because I just wanted to sing pop music better."

Still, the high school teacher persuaded Florez to try out for the National Conservatory of Music in Peru, and he got in.

"There I discovered the world of classical music," Florez says. "But even when I was in the conservatory in Lima, at 17 and 18, I didn't think I was going to become a tenor and sing in important opera houses. Never, never."

Florez came to the attention of Andres Santa Maria, the Peruvian National Chorus director.

"I studied with him arias from [Handel's] Messiah and other works that had coloratura," Florez says. "And right away my voice got used to it. I liked how my voice was developing."

That development earned him a scholarship to the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, where he sang leads in student productions of such bel canto works as Rossini's The Barber of Seville. "I got much, much better," he says. "I was lucky the operas I did were good for me."

Overnight sensation

The luck continued when Florez met tenor and Rossini specialist Ernesto Palacio in 1994. Palacio became Florez's manager and helped get him a small assignment at the Rossini Festival in Pesaro, Italy. The result was much bigger: Stepping in for an indisposed singer and learning the tough tenor lead in Matilde di Shabran in 1996, the 23-year-old Florez became something of an overnight sensation.

Contracts from La Scala in Milan, the Metropolitan Opera in New York and Covent Garden in London soon arrived. Few singers in recent times have generated so much buzz so quickly.

"He is one of the three or four most exciting tenors of his generation," Domingo says. "His brilliant singing, as well as his acting, his charisma and his personality, conquer the public as soon as he is onstage."

Italian conductor Riccardo Frizza, who will lead the Washington performances of L'italiana and who collaborated with Florez on a sizzling Decca recording of Donizetti and Bellini arias, is another admirer.

"I think the agilita [agility], the coloratura and the high notes are what makes the difference between Juan Diego and other tenors," Frizza says.

Some vocal music fans measure tenor quality in terms of wattage - the louder and richer, the better. Florez falls into a more specialized category that the Italians call tenore di grazia - tenor of gracefulness.

Such a tenor cannot tackle the heftier roles, such as the crowd-pleasing heroes Radames in Verdi's Aida or Cavaradossi in Puccini's Tosca.

"Maybe this type is not as widely appreciated by the public," says Christina Scheppelmann, director of artistic operations at Washington National Opera. "But, personally, I'd rather hear someone who sings as effortlessly and musically as Juan Diego does, than someone who hacks his way through a Cavaradossi."

Florez doesn't worry about what other tenors sing. "I value all operas that are good for me," he says. He talks about adding some Mozart, as well as Verdi's Rigoletto and maybe a French opera, such as Bizet's The Pearl Fishers.

Florez also likes a particular aspect of bel canto that isn't available to the Cavaradossis of the world - ornamentation.

Arias in typical Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti works allow singers to add ornaments when melodic lines get repeated, a practice that can make the music more interesting and personal.

"I like [ornamentation] because you can show off your voice even more," says the tenor, who usually writes out his own ornaments in advance. "But sometimes I improvise at the moment. You should see the conductors' faces when I do. One conductor looked very frightened."

Another time, Florez was the one who got a scare. Halfway into an elaborate ornamentation, he realized: "This is not from this opera." He was singing an ornamentation from another aria.

"It is important to know the music very well," he says. "If not, you won't be able to improvise something to come out of a mistake like that."

Musical mistakes seem rare for Florez - "I'm just stunned by his perfectionism," Scheppelmann says - and his reliability helps to explain his success.

He has become highly valued for the totality of his art - voice, technique, style and acting.

Those qualities make him ideal for the role of Lindoro in L'italiana, which he sang to acclaim at the Metropolitan Opera two years ago, opposite the same stellar Russian mezzo who sings Isabella in the Washington production, Olga Borodina.

Tranquillity

When he's not working, Florez likes to head for a body of water. "To rest, I have to be at the beach," he says. And, although his schedule doesn't permit much time for seaside relaxation, he does have some welcome company as he moves from gig to gig.

"I have a girlfriend," Florez says, "and we travel together everywhere. I'm lucky." Is marriage in the offing? "I think someday. I want to have kids and all that."

Meanwhile, there's all that bel canto to pursue.

"The repertoire is vast," Florez says, "but the career is long - or should be. I have a lot of time to sing that repertoire."

He can count on plenty of attention as he does so.

"Everybody talks about you more and more, and everyone expects a lot from you," he says. "Of course, this means more pressure and responsibility, but I take it with a lot of tranquillity. I think that, in a way, pressure works well for me. It gives me an extra push, keeps me going, always trying to be better."

"Ich wollte Rocksänger werden ..."

Sebastian Hammelehle and Max Dax, Die Welt am Sonntag, 2 July 2006

... doch dann wurde Juan-Diego Florez Tenor. Heute gilt der Peruaner als einer der besten Sänger seines Fachs. Ein Gespräch über die Strapazen der Arbeit, die Nachteile der italienischen Küche und die klassische Musik.

In Wien ist es unerträglich schwül. Der Peruaner Juan-Diego Florez, wichtigster Rossini-Tenor unserer Zeit, betritt in Cowboystiefeln, Jeans und rosafarbenem Leinenhemd die klimatisierte Interview-Suite. "Es ist unerträglich heiß in meinem Zimmer", sagt der 33jährige. "Wäre ich reich, würde ich hier wohnen." Wie gut, daß wahre Stars stets aufmerksame Menschen an ihrer Seite haben, die Gedanken lesen können. Die Dame, die Juan-Diego Florez betreut, beginnt im Hintergrund zu wirken. Immer wieder wird das Gespräch durch eingehende Telefonanrufe vom Hotelmanager unterbrochen: Schließlich bekommt er die Suite. Als "Aufmerksamkeit".

Welt am Sonntag: Senior Florez, Sie wohnen in Wien genau gegenüber dem Opernhaus. Ist es das, was ein gutes Hotel ausmacht: kurze Wege?

Juan-Diego Florez: Es ist sicherlich ein Vorteil - zumal, wenn man so viel reisen muß, wie ich es tue. Erst kürzlich habe ich mir in Pesaro ein Haus gekauft, um zumindest während des alljährlich dort stattfindenden Rossini-Festivals vor Ort wohnen zu können. Ich bin sehr glücklich über mein neues Haus: Es liegt direkt am Wasser, in einem entlegenen Teil von Pesaro. Mein Haus in Bergamo sehe ich so selten!

Mit anderen Worten: Sie kehren dem Festival, dem Sie 1996 mit der Aufführung von Rossinis "Matilde di Shabran" Ihren internationalen Durchbruch verdanken, nicht den Rücken?

Florez: Ich bin seit 1996 jedes Jahr in Pesaro aufgetreten. Nur diesen August mache ich eine Pause. Ein Haus in der Nähe des Auftrittsortes zu haben bedeutet für mich vor allem eins: Ich kann selber kochen. Der große Nachteil von Hotels, selbst der besten, ist der, daß man dort nicht kochen kann. Und damit einhergehend kann man auch keine Freunde zum selbstgekochten Essen einladen.

Wie wichtig ist Kochen für Sie als Sänger?

Florez: Immens wichtig! Ich liebe es kompliziert zu kochen - da es mir ermöglicht, meine geistige Rastlosigkeit in den Griff zu bekommen. Ich kann durch das Kochen meine Gedanken fokussieren, mich konzentrieren, den Kopf beruhigen. Kompliziert kochen heißt für mich zum Beispiel: in Italien peruanisch kochen. Italienisches Essen schmeckt auch gut, ist aber zu einfach zubereitet, nicht kompliziert genug. Außerdem ist es in der Regel zu schnell angerichtet.

Ist Kochen für Sie also wie eine Art Meditation?

Florez: Ganz genau. Für mich kommt es der Vorstellung reiner Entspannung nahe, wenn ich ein komplexes Gericht perfekt kochen möchte. Es mag paradox erscheinen, aber es ist zugleich eine Art Übung, denn Perfektion heißt nun einmal Perfektion - die Eliminierung aller Fehler. Das erfordert wie das Singen totale Konzentration, nur daß es mich seltsamerweise nicht anstrengt.

Sie können Ihre Arbeit normalerweise nicht ausblenden?

Florez: Ja. Da ich mir in meinem Beruf keinen Fehler erlauben darf, denke ich tagein, tagaus unentwegt an meine Partituren. Ein Moment der Ruhe - und ich ertappe mich, wie ich im Geiste Noten lese. Nicht besser wird es dadurch, daß ich viele Angebote erhalte. Jedes Angebot kann ein richtiger oder ein falscher Karriereschritt sein. Man lehnt kein Angebot einfach ab - ebenso wenig wie man gleich zusagt. Nach einem Arbeitstag in ein gutes Restaurant zu gehen, empfinde ich daher im Vergleich zum Kochen nicht unbedingt als Ausgleich.

Wie wichtig ist es, in Gesellschaft zu kochen?

Florez: Sehr wichtig! In Peru war es bei uns früher immer so, daß einer seine Gitarre mitbringt - und früher oder später zu singen beginnt: peruanische Balladen, Rocksongs, Volkslieder. Essen, trinken, kochen und singen gehören zusammen. Zumal in meiner Familie: Mein Vater Rubén ist ein in Peru bekannter Volkssänger. Und um ehrlich zu sein: Seit meine Familie in alle Winde verweht ist, vermisse ich diese lustigen, sentimentalen Trinkabende.

Fühlten Sie sich damals schon angezogen von der europäischen Klassikmusik?

Florez: Ehrlich gesagt: nein. Es gibt überhaupt nur wenige Peruaner, die sich für klassische Musik interessieren.

Sentimiento over you

Warwick Thompson, The Times, 22 July 2006

Cheap isn't a word often associated with the handsome young Peruvian tenor Juan Diego Flórez. No, his refined voice shines with the warm lustre of polished gold, and every time he announces another appearance at Covent Garden you can almost hear the boxoffice tills ringing a celebratory carillon to welcome him. But he's not afraid to play the populist: "There's a song I sing called Ella that's so passionate and exaggerated, it's easy to get cheap goosebumps," he says. Then he pauses, and I assume he's going to tell me how he avoids such vulgarity. "Cheap goosebumps, but great ones!" he continues in a low Spanish purr.

Ella is one of the tracks on Sentimiento Latino, an album on which he brings his high, liquid sound to passionate boleros, foot-stamping tangos and criollo waltzes from Peru, Mexico and Argentina. A selection of songs from the album forms the backbone of his Prom concert on Tuesday, but he will also be performing three opera arias from his more traditional repertoire (among them Donizetti's Ah! mes amis, a number containing nine death- defying top Cs).

It might seem that Sentimiento Latino is something of a new departure for the singer. He is, after all, universally regarded as the world's best bel canto tenor, specialising in the operas of Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini. But when I catch up with him in Zurich (and find him looking remarkably cool and collected despite the sticky heat) to discuss the new repertoire on his CD, he's keen to stress that it's not a departure at all.

"My father Rubén was a professional singer specialising in these songs, and he taught them to me as a child," he says. "It's popular music, but my father sang them with real taste and care for the phrasing. He once said he didn't sing with the 'hips' of the voice!" Juan Diego's mother also had a hand in nurturing her son's repertoire. She worked as an administrator for the bar of a big hotel, and whenever the main entertainer got sick she called on her son to cover for him. Although the 15-year-old Flórez was also in a rock band, for a polite hotel audience he naturally sang the crowd-pleasing songs that his father had taught him.

But if the repertoire is more of a homecoming than a departure, it's also part of a mission. "Lots of Peruvians look to America for their music, and they don't care about our native songs. But I care about my roots. I'm trying to save these pieces and preserve them for a new generation."

It might sound over-ambitious, but if anyone can be a Peruvian musical saviour it's probably 33-year-old Flórez. The attention that he has received in Europe and America has made him a hero in his homeland. And since his homeland is a country struggling with debt, corruption and the needs of the Amerindian majority, heroes are a welcome commodity. "Yes, they seem very proud of me," he says thoughtfully. "I think I symbolise a kind of hope."

He has certainly earned his place in the sun. From what he calls a lower-middle-class background, he had no formal musical training until he was 17. It was only then that he decided to study harmony and singing to be a better pop musician. However, at the National Conservatory of Music he somehow got the classical bug instead. "There's no livelihood for classical musicians in Lima; all the players in the orchestra have other jobs, like driving taxis. But I said to my mother I wanted to make a career, and she supported me. I wanted to audition in America, so she sold her car to pay for my fare. It was a great risk."

It was only when all three of the colleges for whom he auditioned immediately offered him full scholarships that he began to realise it was a risk that might pay off. He chose the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia and, with some financial support from wealthy opera- loving Peruvians to cover his living expenses, he studied there for three years. His first big break came at the end of this period in Italy in 1996 when he was just 23. He stepped in to take over the leading tenor role of Rossini's little-performed opera Matilde di Shabran when someone fell ill. He had only a fortnight to learn the role, but he scored such an overwhelming triumph that offers began to flood in from the world's major opera houses. A bel canto superstar was born.

Maybe the Sentimiento album means that a new mariachi star is born too, but anyone fearful that it marks a permanent change of direction needn't worry. Flórez is already booked to appear in a new production of Donizetti's La fille du régiment (which contains the aria with the nine top Cs) at the Royal Opera in January, and there will be plenty more bel canto after that.

His diary is solid until 2013. Does it get easier? Do the technical difficulties fade the more he encounters them? "It's a question of emotion," he says. "You have to control your emotions, because if you emote too much, the voice responds by singing lower and you need to keep a high, forward sound. You can't just sob, like you can in Puccini. But the trick is to put the emotion in the technique, in the legato, in the coloratura. And when your technique gets better, hopefully you can forget about it."

As he's talking, it suddenly seems to me that what he's saying about technique and emotion could equally well apply to all of his life. He is restrained in his manner, but it makes his charm all the more attractive; his bearing is dignified and quiet, but it only seems to focus his energy. Will this help him to bring the music of his homeland alive at the Prom? "When you really sing these songs, you have to forget about your voice," he replies. "You have to let your guts out."

Forget about his voice? With an instrument as distinctive, luxurious and yes, expensive as his, I doubt there will be many people in the Albert Hall doing that.

Flórez confiesa que siempre le gustaron los Rolling Stones

EFE, 20 July 2006

El tenor peruano Juan Diego Flórez se confiesa admirador de los Rolling Stones porque en su infancia creció "con la música popular y escuchando géneros como el rock", dijo hoy a Efe en una entrevista.

"Para mí la buena música es la que está bien hecha, no importa el género al que pertenezca", declaró el tenor, de 33 años, quien la próxima semana participará en los conciertos de música clásica Proms de la BBC en Londres.

Prueba de este vínculo con la música popular es su último disco "Sentimiento latino", que salió a la venta el pasado marzo, "dedicado a lo latinoamericano, a lo español", explicó.

"La música popular está muy vinculada a la música clásica", comentó Florez, que en su juventud cantaba canciones de los Beatles y de Led Zeppelin.

En cuanto a la ópera, señaló que su "estado de salud" es bueno porque "cada vez hay más teatros, aunque conlleva un peligro porque aumenta la demanda de cantantes".

Ese crecimiento de la demanda de artistas hace que "muchos cantantes se lancen al ruedo sin la preparación suficiente", explicó el peruano, que también advirtió de la escasez de profesores de canto.

Si Flórez es conocido por algo es por ser uno de los mejores intérpretes de las óperas de Rossini y por haber sido nombrado por el propio Luciano Pavarotti como su sucesor.

"Pavarotti siempre fue un ídolo para mí y es un premio que ese superhéroe te nombre su sucesor", dijo Flórez.

Además, el italiano es "un tenor lírico puro mientras que yo soy un tenor ligero, por lo que lo normal hubiera sido que se hubiera fijado en alguien que cante como él y que interprete su repertorio", agregó.

El tenor peruano cumplirá el próximo agosto diez años de carrera musical de los que -asegura- está "muy contento".

"Ahora me siento más seguro sobre el escenario, tanto técnicamente como actuando, aunque soy muy autocrítico y creo que siempre hay sitio para seguir aprendiendo".

El cantante dijo a Efe que con diez años de carrera todavía se considera "joven y queda campo por recorrer", y apuntó que tiene "muchos proyectos personales", aunque su agenda está repleta hasta el 2012.

"Me gustaría hacer algo de beneficencia en Perú y tengo proyectado organizar en julio de 2007 un concierto popular para recaudar fondos para los niños pobres de mi país", anunció.