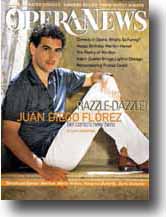

Cover Story: High Jumps

John Morrone, Opera News, January 2004

Cover Opera News January 2004

Juan Diego Flórez vaulted to the top of the international bel canto heap while he was still in his twenties. This season at the Met, the Peruvian-born dazzler is Almaviva and L'Italiana's Lindoro. JOHN MORRONE finds out what's next for everybody's favorite Rossini tenor.

The tenor's pretending to be drunk. Pitching from side to side, brandishing a sabre, he sings while he swaggers and jumps like a cat from the stage to a tabletop, his body as lithe and poised as a dancer's. This is Count Almaviva, relishing a knockabout moment in the Met's production of Il Barbiere di Siviglia, and the tenor is Juan Diego Flórez.

Such acrobatics among tenors are more often associated with the up-and-comers who'll try anything to make a dramatic impression as they deliver some wild and woolly singing. Not so here. What immediately distinguishes Flórez (who made his Met debut in 2002, as the Count, the role in which he returns to the house this month) is the uncommon maturity he brings to the character. One moment he's the privileged aristocrat, every inch a grandee of Spain, the next he's the ardent lover, equal to any stratagem that will win him his Rosina. Equipped with a ringing timbre and seamless coloratura technique, Flórez shapes the Count's music with a high degree of precision and style. His performance in this role is but one of many reasons he's quickly established himself as the most charismatic of today's tenori di grazia (literally "tenors of grace" high-lying, youthful and sweet). Preeminent Rossini scholar Philip Gossett recently remarked, "Juan Diego is a truly elegant singer, which is rare in any circumstances, but he also possesses a nobility, physically as well as vocally, and he's absolutely right for Rossini."

On the cusp of his thirty-first birthday (January 13, 2004, for those who wish to take note), Flórez has been compared with Luigi Alva (his fellow Peruvian), Cesare Valletti and Gianni Raimondi elegant singers all, who distinguished themselves as the Almavivas, Elvinos and Lindoros of their day. But Flórez's extraordinary vocal agility enables him to sing music that, for the most part, eluded those singers. Under the guidance of his mentor and manager, the retired tenor Ernesto Palacio (another Peruvian), Flórez has in the seven short years of his international career pretty much eclipsed even his more recent competition: the accomplished likes of Dalmacio Gonzalez, Rockwell Blake and Chris Merritt. (Perhaps only the charming, vastly underrated Ugo Benelli has demonstrated the vocal beauty and resources to match Flórez's Almaviva.)

Since the moment most CD-listeners first heard him, supporting Vesselina Kasarova on her RCA album of Rossini solos and duets, and performing one bravura aria in the small part of Marzio in Mozart's Mitridate, Re di Ponto, his recordings for Decca have included two recitals one of Rossini fireworks, the other devoted to Bellini and Donizetti and contributions to a volume of Rossini cantatas that featured Cecilia Bartoli. The reviews for his recitals caused a stir, and he was even described by The New York Times (with something of a raised eyebrow) as a "male Cecilia Bartoli."

Flórez is more than a little astonished at his quick ascent, from the fellow who sang in Lima's piano bars to primo uomo everywhere. He's quick to acknowledge that life imitated art in 1996, when circumstances gave him a 42nd Street-style push into the limelight: cast in a minor role in the Rossini Opera Festival of Pesaro's revival of Matilde di Shabran an 1821 super-rarity no living audience had ever heard he replaced an indisposed Bruce Ford on scant notice. When Flórez hears a recording of that performance, he says (with a shuddering laugh), "I was o.k. o.k. because people knew I was young and inexperienced and replacing someone else, and I was singing such difficult music well enough." Very modest words, considering that Flórez admits, "If you saw the score, you wouldn't believe it."

Almost immediately, Flórez was tapped by opera houses throughout Europe to fill some of the highest-flying, most florid tenor parts in the bel canto repertoire, among them Tonio (La Fille du Régiment), Giannetto (La Gazza Ladra), Idreno (Semiramide) and Lindoro in Paisiello's Nina, and to create the role of Count Potoski for the world premiere of Elisabetta, a long-lost Donizetti work that was never given in the composer's lifetime.

During a telephone conversation between performances of Barbiere in Vienna, Flórez ponders the rocketing course of his career to date. "I think on many occasions you need emergency situations a replacement, for example to burn three or four years [preparatory time] off your career," he reflects. Reminded that world-class artists such as Renée Fleming faced years of rejection before achieving success, Flórez ruefully agrees. "There are singers who have a lot of talent, but there are very few people out there who can really see instantly that a person has talent. They work and work, and nothing happens, and then suddenly ... right? In my case, that didn't happen. I was perfectly unknown, and I wasn't singing then like I'm singing now." Were he not such a quick study, and without the good fortune of that "emergency," Flórez has no doubt that it would have taken him much longer.

Just how did a well-brought-up teenager, son of a popular Peruvian singer (Ruben Flórez), with a curiosity about music, an inkling he had a voice, and not much cash in hand, make the leap to opera, let alone the bel canto stratosphere?

"It's difficult to explain, because I don't understand it myself. I always wanted to learn all aspects of music. I played the guitar, learned to read music, wrote songs. During my last two years in high school, a teacher wanted to do zarzuela and mounted not whole zarzuelas but bits of them, and he would give me some roles to sing, in kind of an operatic way. I got interested and had some lessons, which I thought would help me sing better my own pop songs. I was singing better, but it was not the kind of training for an aria. I owed him a lot of money for the lessons, and as he was getting a little ..." he leaves the adjective unspoken "he said, 'If you are not able to pay, you can go to the Lima Conservatory, which is free.' And, so I could audition, he taught me two arias, Schubert's 'Ave Maria' and 'Questa o quella' from Rigoletto, and I got in.

"But the first year there, I didn't want to do opera, I didn't even know opera. I continued to do my own thing, singing in piano bars, and I was learning some arie antiche in my lessons. Others said that I should go to the conductor of the national chorus. He taught me for three years and put me in the chorus. It was there I became involved with classical music completely, singing every day pieces by Mozart, Beethoven, Bach, and at the same time having lessons in and out of the conservatory. The chorus also sang in the opera company that Luigi Alva [organized] every year in Lima. That was my introduction to opera the zarzuela Luisa Fernanda, The Magic Flute and I got used to being onstage, in the chorus, of course. I never sang opera solos in Lima.

"Later, when I applied to Curtis [Institute of Music, in Philadelphia], the arias I auditioned with were oratorio arias by Handel and Haydn. My teachers had played CDs for me, and I heard Barbiere with Alva and L'Italiana in Algeri with Palacio [who was later one of Flórez's instructors at Curtis]. My first contact was not with Verdi or Puccini but with Haydn, Rossini, Mozart, Handel, so that's why I like this repertoire, and I don't want to change it. It's the repertoire that first grabbed me, the bel canto.

"I was twenty when I came to Curtis, and I had not even sung three arias in a row, and this was rough. They handed me a bunch of scores and said, 'These are the operas you have to learn,' and I said, 'What?!' I had to learn I Capuleti e i Montecchi in a couple of months, from September to November 11, when I sang it onstage. My life has been like that since then, because everything has been to 'burn stages.'" (This is a particularly apt phrase that Flórez uses to mean "break in.")

For all the seemingly breathless pace of the Flórez story arc (he claims he's virtually never to be found at home in Bergamo, although it's thirty minutes from La Scala, which he calls his "second home"), his career is settling down as he concentrates on the Rossini roles, as well as more Bellini and Donizetti. (Upcoming debuts include I Puritani's Arturo in May and, in 2005, his first Nemorino in L'Elisir d'Amore both in Las Palmas, where he unveils all his new roles, as an homage to his late role model, Alfredo Kraus, who was born there.) And unlike certain more reckless singers, this is not the kind of tenor who puts the role before the voice.

"You have to consider many things when you want to sing an opera. For example, Rigoletto I could sing very well. It's not heroic, the tenor is a young man, he sings very high 'La donna è mobile' is like a canzone so it's a role for me. But the public is used to hearing certain kinds of singers in the role, so although I could do it, they have their own expectations. And there's no point in rushing into roles. I was supposed to do Les Pêcheurs de Perles, but I didn't, because it was a little heavy. Nowadays we have 'territories.' With your voice you sing this, and with your voice you sing that, but in a way [such restrictions] keep your voice healthy.

"The repertoire I sing how can I put it? the voice is one kind of voice. It continues to be that kind of voice. It doesn't change that much. You don't go from a light tenor to a lyric tenor, or from a lyric to a spinto tenor. Maybe as the voice gets older it gets a little bit heavier, because it's lost a bit of flexibility. It depends on the muscles. That's why tenors move away from a repertoire that includes La Fille du Régiment, which is quite high. I think that the aim should be to sing the repertoire I sing now, and to keep the voice as it is as long as possible. At the end, that's the repertoire that has made me known Rossini, Donizetti, it's thanks to them I'm around! People appreciate me for that repertoire, so I want to sing it for many more years. I know that in time it's going to be difficult to sing certain operas that I now sing easily, but I'll move to others that don't demand as much agility, like more Donizetti stuff, L'Elisir d'Amore, Don Pasquale. These are already in my repertoire, but the roles are not as 'virtuoso.'"

Flórez has never felt the call to sing Lucia's Edgardo, something that was obligatory, he has said with a groan, for tenors like him in the 1950s and '60s, but which nowadays can be well cast with others. "Today," he observes, "you can do Semiramide in many theaters, [Rossini's] Otello at Covent Garden, Le Comte Ory in Pesaro." Alas, there is not so much opportunity in the U.S., where, as he charitably puts it, "They target the better-known repertoire so there's not a lot of call for bel canto and Rossini."

Flórez especially enjoys being in New York, where his mother, who now lives in North Carolina, and other family members can easily visit him. This month brings his New York recital debut at Alice Tully Hall, February his Lindoro in the Met's revival of L'Italiana which, like Cenerentola's Don Ramiro, is a smallish part in an opera dominated by the mezzo-soprano, but in which Flórez makes a huge impact. All the same, he confesses that Almaviva is indeed his signature role.

"I love that role. It's so much fun, because you get to act a lot comically, of course. And when he's not in disguise, he's used to his station as an aristocrat. You know, the Spanish grandees were the only people who didn't have to take their hats off to the king. But at the same time, he's a young man, and he's willing to have some fun, so he misbehaves."

What about that big jump in the drunk scene? Did that originate with the Met's production, or does it come from him?

"Oh, that's me I do it whenever I sing Barbiere. And it's not such a tall table to jump onto. I have an ability to jump high. With both feet, without a running start."

An ability to jump high. For this coloratura tenor, that's putting it mildly.

This page was last updated on: March 21, 2004