This page was last updated on: May 23, 2008

ARTICLES & INTERVIEWS

La Fille du régiment at the Metropolitan Opera, April - May 2008

Photo by Johannes Ifkovits

Opera News, April 2008

Frisky Young Tenors on Operatic War Horses, New York Times, 20 April 2008

Ban on Solo Encores at the Met? Ban, What Ban?, New York Times, 23 April 2008

Keeping It Light, Opera News, April 2008

Fast Chat: New Hero of the High C's, Newsweek, 5 May 2008

_______________________________________________________________

Frisky Young Tenors on Operatic War Horses

Matthew Gurewitsch, New York Times, 20 April 2008

Nine bull's-eye high C's fired off with parade-ground panache: this is what the aria "Ah, mes amis" demands of the bumpkin Tonio in Donizetti's screwball comedy "La Fille du Régiment." Most tenors are thrilled to get through it once.

In February 2007 the Peruvian tenor Juan Diego Flórez made history at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, when he nailed it twice. The last soloist to sing an encore on that hallowed stage was the Russian basso Feodor Chaliapin in Rossini's "Barbiere di Siviglia" in 1933. The ban on the practice goes back to Toscanini. Since then only the chorus "Va, pensiero," the song of the enslaved Israelites in Verdi's "Nabucco," has been repeated. Italians regard it almost as their second, superior national anthem.

"Such an uproar," Mr. Flórez said this month at the Metropolitan Opera, between rehearsals for Laurent Pelly's production of the opera opposite the scene-stealing soprano Natalie Dessay as Marie, the Daughter of the Regiment. (The premiere is on Monday.) Mr. Flórez had just flown in from Lima, Peru, where he had not only sung his first Duke in Verdi's "Rigoletto" but also exchanged vows with the German-born Julia Trappe. The wedding was an encore too, the couple having been married privately last April in Vienna. Their ceremony at Lima Cathedral, the first wedding there since 1949, had the news media in a frenzy.

"I'd done encores of 'Ah, mes amis' before," said Mr. Flórez, 35. "Many times, in Bologna, in Genoa, in Lecce, in Japan. But Milan can be a little snobbish. There's an effort there to put singers down a bit. I couldn't believe the fuss." Even sports magazines took notice, comparing Mr. Flórez to Maradona. A replay at the Met is not impossible. The company's general manager, Peter Gelb, says the house has no policy in this matter.

The last Tonio to knock the world on its ear was the very young Luciano Pavarotti, for whom the lyrical Donizetti was a stepping stone to the heavier Verdi and Puccini. Mr. Flórez is a different creature entirely: a dedicated bel canto specialist, fluent in scales, runs and fancywork far beyond Pavarotti's comfort zone.

The charismatic example of Mr. Flórez is inspiring a whole new generation of tenors, among them two Americans: Lawrence Brownlee, 35, often tapped for productions when Mr. Flórez moves on; and Alek Shrader, 26, now at the Juilliard Opera Center, where in November he sang the fiendishly difficult title role of Rossini's "Comte Ory," an opera expected at the Met with Mr. Flórez in 2010-11.

Last season Met audiences witnessed Mr. Flórez in all his glory as Count Almaviva in "Il Barbiere di Siviglia." His performance crested, as Rossini intended, with the eight-minute pyrotechnics of "Cessa di più resistere."

That aria, the opera's last, establishes Almaviva, rather than the barber Figaro, as the true hero of the story. Yet "Barbiere" (which received its premiere under the title "Almaviva") was long performed without it. As recently as 1988, when the American tenor Rockwell Blake reintroduced "Cessa di più resistere" at the Met, its novelty value occasioned a news release.

In the latest production Mr. Flórez included it as a matter of course, bringing down the house. "Very early in my career, I got used to singing my parts without cuts," Mr. Flórez said. "The decision was not only mine. Ernesto Palacio always pushed for that."

A former bel canto tenor and fellow Peruvian, Mr. Palacio has acted as teacher, agent, adviser and confidant to Mr. Flórez throughout his career. He is one of several forerunners Mr. Flórez acknowledges: in the 1950s, Luigi Alva, another Lima native; in the 1970s, apart from Mr. Palacio, Francisco Araiza, a Mexican.

"They had wonderful polish and style," Mr. Flórez said. "Then, at a certain point, the Americans came in: Rockwell Blake, Chris Merritt. They sang with such virtuosity. It was the first time people heard singing with such breath control, rapidity, color. I'm lucky to come after them. I like to listen, to study. I see a span of development, which I am part of. I have learned from what they created."

But unlike his predecessors, who wowed the experts, Mr. Flórez also has mass appeal. In a recent call from Seattle, Bartlett Sher, who directed him in the Met "Barbiere," described the Flórez effect. "Juan Diego is fun to watch," Mr. Sher said. "He has a great, very natural confidence and a relaxed nobility, together with what Noël Coward would call a little twinkle: something slightly wicked and playful and fun. He has a delightful sense of entitlement onstage, and he never makes singing seem intimidating or too much. He keeps you with him. You feel you could be his friend."

Thanks to Mr. Flórez, opera houses are flinging their doors open to frisky young tenors with agile technique. The bright ones know better than to copy him.

Mr. Brownlee, who won both the Richard Tucker Award and the Marian Anderson Award in 2006, followed Mr. Flórez in the Met "Barbiere" last year, receiving a hero's welcome.

"You won't find a bigger fan of Juan Diego's singing than me," Mr. Brownlee said recently from Toulouse, France, where he was appearing in Rossini's "Turco in Italia." "He definitely raises the standard. He's said that our voices are very similar in certain ways. I think in some ways they are, and in some ways we're night and day. People are always going to compare me to him, because, one, we sing the exact same repertory, and, two, we perform on the same stages. I couldn't compete with him, but it's not about that. I'm so inspired by what he does. He makes me want to go into the practice room and perfect what I do."

Mr. Shrader made his professional debut with Opera Theater of St. Louis in 2006 as Almaviva (without "Cessa di più resistere," which he did sing last month in a broadcast concert with the Valdosta Symphony Orchestra in Georgia). Early in 2007 he appeared with the Gotham Chamber Opera in Rossini's "Signor Bruschino." But his biggest moment to date was on the Met stage as a winner of the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions. There he tossed off stylish, vivid accounts of Mozart's florid "Il mio tesoro" from "Don Giovanni" and that Flórez specialty, "Ah, mes amis."

After a further season in training as an Adler Fellow at the San Francisco Opera, Mr. Shrader will head for Germany, to take up major roles in Rossini and Mozart at a leading house. "Flórez has done what opera companies all over are trying to do," he said recently, "namely to get people to notice opera."

Asked about his vocal models, Mr. Shrader gave Pavarotti pride of place. "I listen to Pavarotti a lot, to be as organic and as easy as he was," Mr. Shrader said. "But it's important to sing in your own voice. No one will sing like him. What you can do is let the music come out of your body as he did."

When learning new roles, Mr. Shrader avoids listening to recordings until he has formed clear ideas of his own. Then he checks them out selectively. "For my own repertory," he said, "I go to Flórez. I go to the best."

Last month, in a Juilliard recital, Mr. Shrader sang a love song from "Barbiere" to his own guitar accompaniment, conjuring up Almaviva's beloved in the balcony so palpably that people turned to see if she was there. To judge by that excerpt, Mr. Shrader is the most romantic Almaviva of these three, the most innocent of heart, for whom the world is new. At the Met, Mr. Brownlee made the sunniest sound, paradoxically coupled with the giddiest temperament, and Mr. Flórez showed the most mercurial personality, the greatest sense of mischief and the fieriest coloratura. Such distinctions make it worthwhile to keep revisiting war horses; by the same token the personalities artists like these reveal can spark life into works long forgotten.

"Matilde di Shabran," for instance, dusted off for the first time in more than a century in 1996 by the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro, Italy. Mr. Flórez was on hand, 23 and fresh from the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where he had completed the training begun at the conservatory in Lima and as a private student of Andrés Santamaria.

Spreading the lessons out over long hours, Mr. Santamaria and the young Mr. Flórez would take time out for cool drinks of whiskey and Coke, rustle up thick steaks and rice, and listen to the kind of singing Mr. Santamaria had a passion for: Bach, Handel, Vivaldi, Almaviva's morning song "Ecco ridente," shot through with the intricate, swift-moving vocal lines that kindled in Mr. Flórez a love for bel canto.

His professional debut was to have been as a walk-on in Pesaro. But Bruce Ford, a noted American bel canto specialist, withdrew on short notice from the role of the woman-hating tyrant Corradino, and Mr. Flórez was pressed into service.

"It's a strange opera," Mr. Flórez said of the experience a few summers later. "There's no aria for the tenor, but the ensembles are phenomenal." Just how phenomenal may be heard on a live Decca recording of a Pesaro revival in 2006. On YouTube the astonishing first stab Mr. Flórez took at the role plays on, epitomizing the confidence Mr. Sher speaks of. The stage-hungry dramatic ferocity is as startling as the technical bravura that makes his lean, intensely focused voice blaze like a hero's.

"I don't like it," Mr. Flórez said the other day. "The high notes are ugly. There's no legato. I like myself better now."

His mantra now is lightness. "When I was in my teens, singing pop music, I tried to make my voice heavy, like a man," Mr. Flórez said, caricaturing the dull, macho sound. "You can hear that on YouTube too. Voices lose agility as they get older. It's common for tenors to lose their high notes, for their voices to get heavier. Many go into heavier parts. But technique is like an antioxidant. It maintains your high notes, your agility. Maybe you need to make more effort."

Mr. Flórez cited the Spanish tenor Alfredo Kraus, an immaculate technician renowned for the freshness of his voice into his 70s. "I will add roles, but nothing heavier," Mr. Flórez said. "I am faithful to my repertoire. That's what I'm known for. That's what people want to hear me in."

Ban on Solo Encores at the Met? Ban, What Ban?

Daniel J. Wakin, New York Times, 23 April 2008

After the tenor Juan Diego Flórez popped out his nine shining high C's in "La Fille du Régiment" at the Metropolitan Opera on Monday night, the crowd rose and cheered. Mr. Flórez obliged with something not heard on the Met stage since 1994: a solo encore.

He sang the aria "Ah! Mes Amis" again, nailing the difficult note a kind of tenor's macho proving ground nine more times. It was one of those thrilling moments that opera impresarios live for.

And, in this case, prepare for. Peter Gelb, the Met's general manager, said on Tuesday that he had asked Mr. Flórez weeks ago whether he would be prepared to repeat the aria, if the audience demanded. Mr. Flórez had already done so at other houses, including the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, where last year he became the first to violate an encore ban since 1933.

Mr. Flórez agreed to Mr. Gelb's request, and the orchestra and chorus were warned. A system was established. Mr. Gelb kept an open line on the phone in his box to the stage manager. After the explosive reaction he gave the stage manager the go-ahead. The manager activated a podium light for the conductor, Marco Armiliato.

Mr. Armiliato held out a questioning two fingers to Mr. Flórez. "He just smiled, and that means 'Yes,' " the conductor said, although Mr. Flórez said yesterday that he did not remember giving a signal. (After the encore, he jokingly held up a third finger.)

Solo encores were common in the 19th century but fell out of fashion as performance practice grew more serious. At the Met they had been explicitly banned for much of the 20th century. Before Monday night the most recent such occasion had been Luciano Pavarotti's repeating the third-act tenor aria in "Tosca" in 1994, Met officials said.

Mr. Gelb said there would be no encore ban on his watch, to make opera "as entertaining and exciting for the audience as it can be."

And the rest of the run? "It always depends on what the public wants," Mr. Flórez said.

Keeping It Light

Tim Smith, Opera News, April 2008

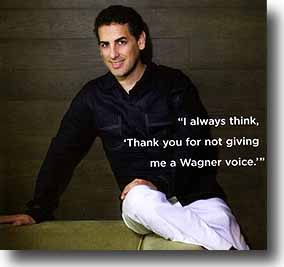

"You are born with a voice, and that voice is meant to sing a certain Fach," says Juan Diego Flórez. "I have a light voice. If you like Wagner and have a light voice, you're going to have a hard life." Sitting in his hotel suite in Miami, where he's appearing in recital at Carnival Center for the Performing Arts (recently renamed the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts), Flórez looks relaxed in a white shirt and form-fitting, rolled-cuff jeans. "Pretty much, I'm doing what I want," he says. "I like very much my repertoire."

That includes his trademark role of the high C-packing Tonio in La Fille du Régiment, which he performs this month at the Metropolitan Opera. "This production is a lot of fun," the tenor says. "I did it in London and Vienna, and the public loved it. They were shouting and screaming." Some of that enthusiasm was certainly generated by the equally starry performance of the tenor's costar, Natalie Dessay, who again joins him at the Met. But it is, inevitably, the lithe and telenovela-sensual Flórez who stops the show with his own risk-taking in the stratosphere-scraping aria "Ah, mes amis, quel jour de fête!" whenever he romps through Fille, a work ideally suited to his light, bright tone and remarkably articulate phrasing. "The opera is a compendium of bel canto chiaroscuro, pianissimi, high notes," Flórez says. "It's very hard to sing, but rewarding. I like Tonio, but more musically than dramatically. He's a nice guy, somebody who's cute. In a way, he's passive. The role is not an active one, like Almaviva, but an observing one. And if that's your role, you don't run around being an actor with it that's a bad actor, no?"

Although a tendency to ham is not a Flórez trait, some Italian critics more or less accused him of just that in February 2007, when he broke a seventy-four-year ban on solo encores at La Scala to deliver a second performance of "Ah, mes amis," with its famous nine high Cs. "I almost always encored it in other theaters, even in Japan, so I thought maybe I would do it also at La Scala," the tenor says. "I was told they are not used to doing that there, and I said, 'No problem.' But on the day of the performance, the artistic director told me, 'Listen, do what you want.' I didn't know about the history of the ban. The next day, it was in all the newspapers 'A Tradition Ended.' I thought, what's going on here? They were calling me even from soccer magazines, asking me if it felt like making a goal."

Two months later, Flórez again offered a bis, this time at the Vienna State Opera, where he had also been told by management that encores were frowned upon. "But the audience asked so long," Flórez says, as his wife, Julia Trappe, enters the room. "There was over five minutes of applause," she adds. The German-born Trappe, who was raised in Australia, met the tenor in Vienna in 2003. "I was studying to be a singer, but I quit, basically, because I felt I couldn't do that and get married," she says. "I feel so honored to be part of the career of Juan Diego, this artist I admire so much." Flórez looks genuinely touched and purrs, "Thank you, baby." As for the operatic reprise in Fille, Flórez insists, "I don't do the encore just for the sake of doing it." The tenor adds, "The second time, I may do more legato. Maybe the second high C won't be brilliant, but" a sly grin breaks out on his face "the sixth!"

From his early days at the National Conservatory in Peru ("I entered to become a pop singer, not a tenor"), Flórez studied arias by Bach, Handel and Haydn. When he met distinguished Peruvian tenor Ernesto Palacio (later his manager as well as mentor), Flórez was given lots of Rossini to sing and found the composer's music to be a natural fit. He experimented with various material as a student in Peru and later at the Curtis Institute ("When I was eighteen, or something like that, I sang "Che gelida manina"), but he kept gravitating back to bel canto.

The tenor's claim on that field has been solidified by many a Barbiere and Cenerentola, not to mention L'Italiana in Algeri, La Sonnambula and Don Pasquale. But, understandably, whenever Flórez appears in Fille, he makes an extra splash. He has what Rupert Christiansen, writing about the tenor's Covent Garden appearance in the opera last year, called "the wow factor" as Tonio, "playing the lad with evident pleasure."

Although he considers the Act II aria "Pour me rapprocher de Marie" even more technically demanding, Flórez is hardly blasé about the challenges of "Ah, mes amis." In the opera house and on the concert stage, he invariably brings to that piece the qualities that make him, as Martin Bernheimer has written, "a compelling specialist in sweetness, lightness and charm" who "appreciates the impact of a high C."

The tenor says, "The high Cs should be like knives. Sometimes, I feel they come very good. Sometimes, I don't find the position. Maybe it's better if you don't try to figure out how you do it. Just leave it there. If you worry about the high Cs, you shouldn't do this opera."

When asked to comment on some recordings by other tenors, Flórez agrees to share his views in a blind listening test. A couple of golden oldies elicit admiring comments. Instantly recognizing the sound of Cesare Valletti, singing the aria in Italian in a 1950 recording, Flórez smiles broadly. "Hear how similar he is to [Tito] Schipa. A very good style. The voice is always ready to make a piano. When you hear singing with this line, this grace, this cleanness of voice, diction and intonation, it is special. This guy understands."

From a live 1960 performance, there's a seriously abridged (minus high Cs) account by Giuseppe Campora. Flórez doesn't recognize the singer but is taken with the art. "A great voice," he says. "It is from another style, a different way of singing. What you hear is elegance, with pianissimi at the end of phrases and a lot of portamento. It reminds me of a Peruvian tenor, Alejandro Granda." There's instant identification and appreciation of Ugo Benelli in a 1966 performance (shortened to only four Cs). "I know Ugo. He is such a good tenor," says Flórez. "This is great singing. Ugo had great high Cs." Flórez listens intently to a live 1970 recording of Grayson Hirst, a tenor he has not heard before: "I can tell he can go very high. He has a facility for climbing up. It sounds easy. And he sounds more French. The aria is easier to sing in French."

Flórez knows in half a note that the next singer is one of his heroes, Alfredo Kraus, heard in a 1991 concert: "You can see how he maintained the voice. When he goes up, see how the voice blooms. To sing at that age [sixty-three] is phenomenal. Kraus did a lot of sports. I try to keep up on sports and exercise, too. If you don't have a good technique, good breathing, nothing works. I don't know if I'm going to be still singing at his age." Flórez gestures toward the big window behind him and the vista of tropical relaxation outside. "I'm not sure I'd even want to."

As Fernando de la Mora, on a mid-1990s recording, launches into the aria, Flórez smiles approvingly. He doesn't know the vocalist but quickly guesses that the Mexican-born tenor is a Spanish-speaker. "This is a bigger voice, with a good position. The Cs are very good. He's more lirico."

And then, the unmistakable voice of Pavarotti fills the room. It's a live recording from 1969, sung in Italian. "This is also a heavier voice. It can bloom in high register, but some notes are harder than for a light tenor. Some things may not be perfect, but you hear the spontaneity of Pavarotti. He just goes and sings it." Pavarotti reaches the lilting "Pour mon âme" portion of the aria ("Qual destino" here). "He always goes very fast here. I can go slow, because I'm very comfortable. It's resting time for the high Cs. The way he accents the Cs gives you the excitement. The last is not stable, but it doesn't matter. He tended to stand up there and sing to you. It was so immediate. You hear he is happy. He was my complete idol, no?" With that, Flórez jumps up to a nearby table and types quickly into a laptop, producing in seconds a download of Pavarotti's Tonio in 1966 at Covent Garden. "The last note was not quite solid there either," Flórez says, "but the performance is so exciting."

Early in Flórez's career, he received a sizable ego-boost from Pavarotti. "He declared that the tenor among the newcomers who could become the next star was Juan Diego Flórez. I was surprised. Here was my idol speaking about someone who did not sing the big repertoire that he sang. I wouldn't expect a tenor like him to appreciate me. I talked to him on the phone after I heard about his comments, and he said, 'It's true. You are the champion.' He never said, 'But you should sing this or sing that.' I saw him the last time on the thirty-first of July in Pesaro. My wife and I ate dinner with him," Flórez says. "It was the last time he dined sitting at the table. He was not comfortable but very simpatico and joking. Then he went to Modena, and he died before we could see him again."

Flórez has always been sure of his vocal path, which moves steadily through the bel canto field of Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini. The repertoire "is like sport. I don't want to say like a circus, but there is some kind of that extreme quality in this music, too," he says. "The beauty of bel canto is that you get to do everything legato singing, beautiful romantic moments, florid, heroic stuff. It's always challenging. It was very clear from the beginning that I was good for this repertoire. I started with the Rossini Festival, which was a big statement about the type of my voice." That was in 1996, when, at twenty-three, Flórez replaced an indisposed Bruce Ford in Matilde di Shabran at Pesaro and caused quite a stir. "Now I get to do these strange operas that aren't so much done. I am able to do them because they ask me, not because I force anyone. Theaters are willing to stage them. At the Met, I will sing Le Comte Ory, which you usually don't do in a theater like that.

Other works on the horizon include Linda di Chamounix in Barcelona and Robert le Diable in London and New York. "That could be a little heavy," he concedes. "I know that but there will be a lot of rehearsal, and I will insist on keeping the orchestra down in certain passages." And he will tackle I Puritani, though without the high F. "I go into high register with my natural voice. My top is E-flat. Obviously, there is a mix of head voice, but in my voice it sounds natural," Flórez says. "If I went to an E or F, I would have to go to falsetto, and that wouldn't sound so coherent with the rest of my singing." (The tenor's recent, rarity-filled CD tribute to the legendary Rubini, reviewed on page 75, suggests how much bel canto terrain remains open to him.) As one of the few tenors to hit stardom without a lot of Verdi or Puccini under his vocal cords, Flórez could stay comfortably within this niche as long as he likes, but he plans to stretch carefully in various directions, including Così Fan Tutte and Rigoletto, which he calls "the only Verdi I will do. I think it is for my voice, and I will bring my bel canto background to it.

"I love to go to the Wagner operas," he says, "but I always think, 'Thank you for not giving me a Wagner voice.' You see tenors who sing light repertoire move into lower, heavier repertoire, and although maybe they can do it, you always know it is not right for that voice. When you don't change your repertoire, you can sing very well for a long time. Kraus always had a D 'til the end. The trick is not to thicken the voice. I will sing a few things a little bit heavier, but I will sing it with my voice, never pushing. And if it doesn't go well patience. Singing takes good intuition. Speaking crudely, there are not many teachers with wonderful secrets of the voice. You have to be independent and be a good self-learner."

Fast Chat: New Hero of the High C's

David Gates, Newsweek, 5 May 2008

Peruvian-born tenor Juan Diego Flórez, 35, sang "La Fille du Régiment" at the Metropolitan Opera last week, and was cheered wildly after the showpiece aria "Ah! Mes Amis," with its nine high C's. He then sang an encore, hitherto banned at the Met, with a single exception: Luciano Pavarotti during a performance of "Tosca" in 1994. Flórez spoke with Newsweek's David Gates.

Why have you been the one to break the ban on encores?

I don't know. But since I began singing this opera the public has asked me for an encore, first at La Scala last year, then abroad, even in Tokyo. The word spreads, and it becomes like a tradition. At La Scala I didn't know I was breaking a ban of 75 years. It's better not to know.

Are you hurt now if they don't want an encore?

No, no, no. Because sometimes you're glad you're not doing all those C's again.

Is "Ah! Mes Amis" really as difficult as everyone says?

My repertoire is the bel canto and the high tenor, and in that repertoire everything's difficult. But for me, this piece is not extremely difficult, and often I quite enjoy singing it.

As a teenager, you had a different repertoire.

Yes, in Peru I had my rock band. I played guitar, keyboards, sangI played the drums sometimes.

What kind of guitar?

I don't remember, because it was a cheap one. I didn't have money to buy a Fender. Something without a brand, maybe.

Do you perform tonight?

No. I'm doing an interview with [costar] Natalie Dessay at the Metropolitan Opera Guild. That's my performance for tonight.