This page was last updated on: January 12, 2006

José Carreras in Italy

The 1970's

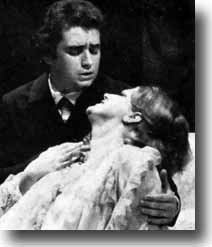

José Carreras and Katia Ricciarelli in La Traviata, Trieste 1976

La Scala Debut 1975

A Spanish Couple for Verdi's "Ballo in maschera" at La Scala, Corriere della Sera, 13 February 1975

Caballé-Carreras triumph in Verdi's Ballo, Corriere della Sera, 15 February 1975

La Scala Debut 1975

INTERVIEW

This interview with Montserrat Caballé and José Carreras was made on the day before his debut at La Scala in Un ballo in maschera The interviewer seems to concentrate exclusively on Caballe rather than on her young co-star. However, after the performance the reviews centered on Carreras - who triumphed in his first appearance before one of the most demanding audiences in the world of opera. You will also notice from Caballe's comments on Carreras' costume, that this must have been before Giuseppe di Stefano lent him his own costume for the performance after seeing the dress rehearsal. The original Italian version, 'Coppia spagnola per il "Ballo in maschera" alla Scala' is available here.

A Spanish Couple for Verdi's "Ballo in maschera" at La Scala

Ettore Mo, Corriere della Sera, 13 February 1975

[English translation © Jean Peccei]

They say she weighs 90 kilos. It's probable. They say that to find her

artistic ancestors you need to look at the angelic stars of the past,

amongst the Malibrans and Pastas. It's true. They say that because of

her love for her art. and despite her tender and placid temperament, on

occasion she knows how to show the lethal claws of the primadonna. It's

highly likely.

Montserrat Caballé, 41 years old, and for some weeks the uncontested

queen of La Scala. After having literally intoxicated the audience and

the critics in Bellini's Norma, and with a recital of brilliant arias,

tonight she will take on the unhappiness of Amelia, fought over by the

tenor, Riccardo, and the baritone, Renato in Verdi's Ballo in Maschera,

directed by Zeffirelli.

The tenor who faces his La Scala 'baptism' is also Spanish. Like

Caballé, he was born in Barcelona. For a while they lived on the same

street. His name is José Carreras, 28 years old, a handsome young

Catalan man; dark and slender, with a voice - they say - that is

reminiscent of Di Stefano's brilliant youth.

Caballé maternally caresses him with her soft glances: she finds him

more handsome than Valentino. "It's a pity - she says - that the

costumes don't do him justice. They are clumsy, oversized, horrendous.

In the first act, when I look at him, he looks like an astronaut. He

would be divine in a 'traje de luz' [the tight-fitting costume worn by

matadors in Spain]. Tonight we will have a Spanish Ballo, or better yet,

a Catalan one. You see, in the opera world, we are the clan of Catalans.

We really are. Right, José?"

Carreras is fortunate. He comes to La Scala young both in years and in

his career. Caballè did not have the same good fortune. She stepped

onto the stage for the first time in 1970 with Lucrezia Borgia, after 13

years of valuable experience elsewhere. How to explain that?

"How to explain that? - she says - Well, with beer. You see, at the

beginning of my career, I sang in Germany and they always understand

things a bit late. The Germans say that you need to drink the beer

there two times to see if it is good or bad. Evidently, that bit of

voice that I let them hear was not enough. They need a second taste and

perhaps I will have to return. I sang the same repertoire that I sing

now, only with a bit more of Mozart and Strauss"

"A real pity, Signora Montserrat. If you had come to Italy, one beer

would have been enough" [Interviewer]

"Instead no, I am happy with this. If I had come to sing here, I would

have ruined myself. Yes, because here, if there is a beautiful voice,

they work it too much. You sing and sing and sing until there remains

nothing in your throat but a croak. Right? [She uses the Spanish word

'verdad']

Montserrat is grateful to Di Stefano, she attributes to him the great

turning point in her career: "Pippo - she says - heard me for the first

time in Mexico, in 1964 if I'm not mistaken. Immediately afterwards he

told impresarios in New York and Dallas about me, his judgement was

highly prized. From that came my first contracts, the big international

engagements. I also owe a great deal to Maestro Siciliani who was among

the first to believe in my voice."

For some years now, everyone believes in her voice. The critics have run

out of heavenly adjectives to describe her, gloomy are those that

cannot find the money to hire her. Caballé is expensive.

To say that she is worth her weight in gold is to undervalue her. As an

artist, she is an exacting one. There are those who see in her sudden

furies the unforgettable ones of the divine Callas.

"Is it like that?" [asks the interviewer]

"Like what?" [answers Caballé]

"There is talk, for example, of a clash with Maestro Molinari Pradelli

during the dress rehearsal for Norma"

She denies this, with an icy glare: "Write instead that I have great

esteem for Molinari Pradelli and that I sang Norma on condition that he

would conduct. He is also conducting this Ballo"

But one thing she does admit: she does not tolerate mediocrity. She is

a priestess of opera, ready for the sacrifice. In carrying out its

liturgy, she is chaste and severe. [here the interviewer is drawing

explicit parallels between Caballé and one of her most famous roles -

Norma, the Druid priestess.] On Saturday evening at La Scala, the

public realized this when at the beginning of the opera, she stopped

the orchestra with sacred authority. The incident has passed into

history in at least five different versions. I recount them to her.

"All of them wrong - says Montserrat Caballé - I'll tell you the true

one. Here it is: At a certain point I could see up in the royal box - or

ex-royal box - a bright yellowish light shining in my face. I was trying

to concentrate myself for 'Casta Diva' [a notoriously difficult aria]

and that light made me lose my concentration. I could also see some

people sitting around a table, shuffling sheets of paper and talking.

Perhaps they were the lighting crew. And so, I made a sign to the

conductor. I told him: I cannot continue until that light is turned off.

The maestro said: "Oh, my God!". Then the audience applauded me and

also the orchestra players; the yellow light was turned off and we began

again"

Some apprehension at moving from Norma to Amelia tonight?

Yes, she says, a lot. "I am always afraid when I sing. Always. [This

second time she uses the Spanish word 'siempre']. Just as I am afraid

when I fly in an airplane. It is the fear of not being up to the

situation, of not giving my best. Until the final curtain falls, my poor

nerves are in a pitiful state. Right, José? Much depends also on one's

colleagues and there are those who will try to undermine you, no?"

But tonight this is not the case. There is amongst the others, José

Carreras from Barcelona, from the clan of the Catalans.

REVIEW

The following is a translation of the paragraph on Carreras' performance on the opening night of Un ballo in Maschera. The full review in the original Italian, 'Caballè-Carreras trionfano nel Ballo di Verdi' is available

here.

here.

Caballé-Carreras triumph in Verdi's Ballo,

Duilio Courir, Corriere della Sera, 15 February 1975

[English translation © Jean Peccei]

[...] One must say immediately that Carreras showed himself to be not only a tenor of extraordinary quality, but also, what is more difficult, to be an authentic Verdian hero. His interpretation is lyrical, intense, and of a purity of emission that recalls that of the incomparable Di Stefano, but his temperament suggests a dramatic definition achieved through an astounding musicality. Carreras's phrasing is blessed with an expressiveness that is a product of nature and style. It makes the drama of Verdi's words completely clear, with an internal grasp of feelings that in the finale of the opera reached a balance of beauty and interior emotion that were simply wonderful. Certainly, we find in this tenor a blissful timbre, sustained by the vigor of youth, that has now proven itself with a degree of daring involvement in the dramatic situation of emotional relationships that is the true heart of the opera. [...]