This page was last updated on: February 3, 2009

REVIEWS

La rondine, New York Metropolitan Opera, December 2008

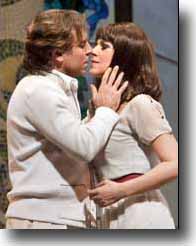

Roberto Alagna as Ruggero & Angela Gheorghiu as Magda

La rondine, New York Metropolitan Opera, December 2008

La Rondine, Metropolitan Opera, New York, Financial Times, 2 January 2009

Star Couple Shine in "La Rondine", Bloomberg News, 5 January 2009

Alagna, Gheorghiu ring in the new year at the Met, Associated Press, 2 January 2009

Puccini and Operetta? He Does It His Way, New York Times, 2 January 2009

Late Puccini with star power, Philadelphia Inquirer, 3 January 2009

La Rondine, Variety, 5 January 2009

_____________________________________________________________________

La Rondine, Metropolitan Opera, New York

Martin Bernheimer, Financial Times, 2 January 2009

La Rondine, back at the Met after a 72-year absence, is Puccini's most eclectic sort-of-masterpiece. Completed in 1917, it makes knowing references some musical, some dramatic to Lehár's Lustige Witwe, Verdi's Traviata, Johann Strauss's Fledermaus and, yes, Puccini's Bohème. For a fleeting in-joke, it quotes Richard Strauss's Salome. The commedia lirica vacillates shamelessly yet elegantly between artificially sweetened verismo and sentimental kitsch. Yet, if performed with taste and style, it can be engrossing.

And so it was on New Year's Eve. Nicolas Joël's "new" production already seen in Toulouse, London and San Francisco plots the conventional action, also the inaction, deftly. Stephen Barlow recreates the master plan faithfully. Ezio Frigerio's picturesque designs and Franca Squarciapino's chic costumes swap the original Second Empire setting for Art Deco excess. Marco Armiliato imposes breadth and warmth in the pit, and accommodates his cast generously.

Yet when all is sung and done, La Rondine remains a showpiece for the diva on duty as Magda, one of those high-priced whores with a heart of gold. Angela Gheorghiu (pictured, with Roberto Alagna) has virtually claimed the challenge as her own, and she devours it with narcissistic brio. In a series of tight gowns bearing daring décolletage, the Romanian soprano glides and slinks about the stage with self-conscious abandon, stretching for applaud-now poses when climaxes loom. Although she may look even better than she sounds (softer high notes would be welcome), she sustains lustre and expressive point throughout.

Alagna, her offstage husband, partners her as an adoring Ruggero who might win more hearts if he balanced ardour with finesse. Marius Brenciu, the second tenor, sustains lyrical charm as Prunier. Lisette Oropesa is winningly winsome as Lisette, the sprightly maid who borrows her mistress's dress (sound familiar?). Vocal unsteadiness notwithstanding, Samuel Ramey represents luxury casting as Rambaldo, Magda's grave protector, and the chorus makes a rousing noise at the Bullier bar (shades of the Café Momus). Puccini's swallow has come home to roost in generally fine fettle..

Star Couple Shine in "La Rondine," Dim Work by Puccini at Met

Manuela Hoelterhoff, Bloomberg News, 5 January 2009

Some 70 years have passed since Puccini's "La Rondine" last appeared at the Metropolitan Opera, and I suspect most of us will be dead by the time another new production creaks to the stage here in Manhattan.

So enjoy the show while it's around featuring two spectacular singers: diva Angela Gheorghiu and her button-cute husband, Roberto Alagna, the only star tenor slim enough for pleated pants.

They sing the doomed couple at the heart of this modest piece composed by Puccini long after "La Boheme" and "Madame Butterfly." This was a time when his spirits were low and soon to dive with the start of World War I, which would delay the world premiere of "Rondine" until 1917. Attacked as a musical fossil, the poor man had cast about for something provocative to set, and perversely ended up writing this old-fashioned opera about an aging kept woman who lives in a huge Parisian mansion thanks to a banker but falls for a sweet young man from the provinces.

The banker, played by Samuel Ramey -- who looks very distinguished in this small, senior role -- is a rather nice guy, I hasten to add, given these delicate times for people in finance.

Dim Dud

"Rondine" -- the title means swallow and refers to the flighty heroine -- was inspired by Viennese operettas and the promise of a huge purse, though it is hard to comprehend how a sophisticated composer came to set a libretto so dim and derivative.

In Act I, Magda is at home receiving friends and warbling on about young love, encouraged by her poet friend, Prunier, and her girlfriends, who usually gesticulate a lot since the writers gave them little to say. At the Met, which updates events from the mid-19th century to the 1920s, they also engage in dramatic smoking.

In Act II, she meets Ruggero at a small cafe. He was actually at her house in Act I, but the librettists -- it took two Viennese and one Italian to write this nonsense -- were presumably too drunk to arrange a meeting.

By Act III, the duo is on the Cote d'Azur, madly in love but running out of money. Then he gets a letter from his parents saying they welcome this pure woman as the mother of his children.

Kids! Gheorghiu's expression of horror was amusing if possibly not intended. Anyway, she reminds him of her colorful biography, makes him weep and returns to the banker. No one dies at curtain time, though given the general lack of drama, a little ominous coughing would have been appreciated.

Puccini Pilfers

A barely sketched subplot features Lisette, Magda's ambitious maid, wearing madame's clothes for a night out on the town and briefly pursuing a theatrical career.

Sound familiar? Yes, though Johann Strauss did a lot better dressing up his maid Adele in "Die Fledermaus," than poor Puccini and his librettists, who further stole part of the plot from Verdi's "La Traviata."

All along, Puccini also pilfers from himself, working in references to his great shows in a way that gives the piece a weirdly embalmed quality. And yet, there are many pages of lovely music with a melancholy flavor, though only one aria is spectacular, "Chi il bel sogno (or dream) di Doretta."

Prunier starts it off in Act I until Magda sidles over to the piano, picking up the tune with swooning high notes. Gheorghiu sang it beautifully and made gorgeous sounds all night long from underneath a very large and ill-advised wig. Alagna doesn't have a great aria, but he pumped up the volume thrillingly in the duets. Of course, the fall/spring aspect of their stage romance is somewhat undermined by the fact that these two are the opera world's most famous couple and both in their 40s.

Nice Conducting

Newcomer Marius Brenciu made an impressive debut as Prunier, and his sidekick Lisette Oropesa was suitably lively as Magda's maid. That wonderful conductor Marco Armiliato brought just the right touch to the score, a lightness that is rather missing from the production, which is curiously grand and glacial. Originally directed by Nicolas Joel, it comes from Toulouse, with stops since then at Covent Garden and San Francisco.

The lovers sing their goodbyes on the terrace of a grand hotel with Tiffany decorations. The cafe is two stories high and filled with stiff-limbed choristers. Couldn't they dance a little? That set looked like it could be nicely recycled into "Aida," and maybe if the Dow drops a few hundred more points it will be.

"La Rondine" opened on New Year's Eve and will be performed eight times through Feb. 26, although Alagna appears only Jan. 7, 10 and 13. The Jan. 10 performance will be telecast live to select theaters worldwide.

Alagna, Gheorghiu ring in the new year at the Met

Verena Dobnik, Associated Press, 2 January 2009

At the end of Giacomo Puccini's "La Rondine," an enamored woman jilts her ardent but poor lover, saying she can't give up her old life as a rich man's mistress. And, she says, she doesn't want to financially ruin her soulmate. But on New Year's Eve, after the Metropolitan Opera's gold curtain fell, there was a second ending: The two lovers went off together into the Manhattan night.

The stars of the company's first production of Puccini's work since 1936 were soprano Angela Gheorghiu and tenor Roberto Alagna married in real life."We can say to the audience, 'OK, they will be separated in the story, but not in real life!" Alagna said in a backstage interview. "And we can go to the New Year's party together!" added Gheorghiu.

The musical power couple has fertilized opera's overripe gossip world over the years most recently in 2007, when Gheorghiu was fired from Chicago's Lyric Opera for missing rehearsals, saying she wanted to support her husband during his Met appearances. Months earlier, he had a dustup with Milan's Teatro alla Scala after walking out of a performance of "Aida" because some fickle audience members booed.

But there's no doubt that the two, who first met 16 years ago on the stage of London's Covent Garden, share a vocal synchronicity and an emotional electricity that keeps an international audience riveted. They proved it Wednesday in a performance of "La Rondine" that would be difficult to match singing with ravishing, tender voices and onstage intimacy they say is not feigned. Their 1997 recording of Puccini's work is considered the best by many critics. Alagna and Gheorghiu were married at the Met in 1996 by then New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani. On Wednesday evening, their love story again spilled onto the stage.

First, she appears at a party as a worldly Parisian woman, Magda, who questions her existence with a wealthy older man while reminiscing about a brief youthful infatuation with a handsome stranger at a dance hall. She barely notices one party guest, a newcomer from the countryside named Ruggero Alagna.

Reading Magda's future in her palm, a poet friend tells her she will someday fly off like a swallow in search of a new true love hence, "La Rondine," meaning swallow in Italian.

In this first scene, Gheorghiu sings the opera's most famous aria, "Chi il bel sogno di Doretta" (Doretta's Dream Song) a fictional woman's dreamy longing for love lost summed up in two falling intervals: a perfect fifth followed by a tritone. Gheorghiu's soaring, gem-like phrases created some magical moments of music.

Magda returns alone to the dance hall, where she by chance encounters Ruggero. They fall in love and she abandons her role of pampered mistress.

This second act at Bullier's dance hall matched the evening, with an oversized mirror ball dangling from the ceiling as Alagna's thrilling upper register opened up for the love duet. Ruggero invites Magda to dance to the strains of "Nella dolce carezza della danza" ("In the soft caresses of the dance"), with tenor and soprano singing sensuously in each other's arms as though transported.

Knowing one another as husband and wife doesn't make working together easier, Alagna said. "The problem is, when you go onstage, you must be surprised," he said. "But we know one another very, very well. I know exactly what gestures she'll make." Surprise is replaced by a more interesting experience for the audience: the feeling of being allowed to peek, unnoticed, at a couple in love at home.

For years, Gheorghiu was more "ashamed" kissing her husband onstage than any colleague, "because the whole world sees my intimacy," she said, adding jokingly, "With a colleague, it's 'Mua, mua, mua salut, ciao, arrivederci!'" For the endless kisses on this New Year's Eve, the Met stage must've been filled with mistletoe.

"La Rondine," premiered in 1917 in Monte Carlo, packs some of opera's most beautiful melodies into just over two hours, along with some complex, modern psychology. In the final act, the deeply-in-debt lovers are living happily together when Ruggero proposes, sending Magda into an emotional spin. She declares herself unworthy of him because of her tawdry past, and despite his pleas, abandons him for the life to which she's accustomed.

Alagna embodied Ruggero's pain with throbbing heartache, his burnished voice blossoming into Gheorghiu's for the ending. The pleasure of performing the scene together "is double," said Alagna. "I cry because all of a sudden, at that instant, it's no longer Magda who is leaving it's as if Angela was leaving." The current Met production was first created for them at Covent Garden in 2002, and repeated in 2007 at the San Francisco Opera.

Making his Met debut on Wednesday was Gheorghiu's fellow Romanian Marius Brenciu, whose clarion tenor fit the role of the poet with velvety lyricism. The veteran bass Samuel Ramey's rich, but now rather wobbly, aging voice was also right for the role of Magda's wealthy lover. Conductor Marco Armiliato led the orchestra, drawing out Puccini's lilting melodies with elegant effervescence.

Puccini and Operetta? He Does It His Way

Anthony Tommasini, New York Times, 2 January 2009

Sometimes, fairly or not, an artistic work gets saddled with a reputation it just can't shake. A prime example is Puccini's opera "La Rondine," which arrived at the Metropolitan Opera for a New Year's Eve gala performance on Wednesday night in a beguiling new production by Nicolas Joël and starring the singing world's much-touted love couple, the soprano Angela Gheorghiu and the tenor Roberto Alagna. Amazingly, this is the first Met production since 1936.

"La Rondine" has long been considered Puccini's problem child, his sole venture into crossover, an attempt to write an Italian operatic equivalent of a lightly comic, bittersweet Viennese operetta. He was invited to create the work in 1913 by the directors of an operetta company in Vienna. He had little sympathy for the genre as it was generally practiced: all those arch comedies with frothy plots, slipshod scores and lots of dancing. He announced from the start that his work would have music throughout and no spoken dialogue.

Still, the idea of writing a lighter romantic opera something with the comic resonance yet musical richness of Strauss's "Rosenkavalier" appealed to Puccini. Though World War I scuttled a Vienna premiere, "La Rondine" had its first production in 1917 in Monte Carlo, neutral territory.

Working with the librettist Giuseppe Adami, he adapted a story about a young Parisian, Magda, the lavishly maintained mistress of a rich older banker, Rambaldo. A modern yet vulnerable woman who harbors fantasies of romantic love, Magda falls for Ruggero, the earnest and adoring son of a respectable family in southern France.

For Puccini, however, love was nothing to joke about, and his attempt to blend soaring lyricism with comedic lightness often seems strained. Still, the opera does appear in production from time to time. The New York City Opera has presented the work several times, most recently in 2004, the same year Mr. Joël's production was introduced at the Royal Opera in London, starring Ms. Gheorghiu and Mr. Alagna.

With the story, originally set in the mid-19th century, updated to roughly the 1920s, complete with Art Deco sets and costumes, this production makes a strong case for "La Rondine" as sophisticated, charming and poignant. Vocally, both leads are somewhat disappointing. Ms. Gheorghiu, as Magda, sings with gleaming sound and wonderfully dusky colorings in the strong top register of her voice. But the earthy richness of her mid-range singing sometimes turns breathy, and her low voice is curiously weak.

Though Mr. Alagna still has glints of the virile tenor of his early years, he seems to be having some technical troubles of late. As Ruggero his singing is uneven, sometimes burnished and steady, sometimes shaky and inelegant.

Yet these undeniably charismatic artists believe in "La Rondine," which they recorded memorably in 1996 for EMI Classics, with Antonio Pappano conducting the London Symphony Orchestra. Their conviction comes through here over all, in stylish and affecting performances. And in costumes by Franca Squarciapino, they look wonderful as Puccini's young lovers.

During the Act I party scene at Magda's salon in Paris, Ms. Gheorghiu, with her dark hair and headband looks like Louise Brooks. And when Mr. Alagna first appears in his tan suit and vest, hoping to make a good impression on the banker Rambaldo, an old friend of his father, he conveys the character's mixture of intimidated awe and eagerness upon arriving in the big city.

The conductor, Marco Armiliato, in what may be his best work to date at the Met, draws a nuanced and supple performance from the orchestra. I thought I knew this score quite well, but have never been so struck by the intricacies of the music.

Puccini's cagey way of creating a light romantic comedy that was also a compelling score was to fill the music with subtle modernistic touches. String harmonies in the orchestra are tightly packed with notes, turning them almost into sound clusters. Orchestral chords move in bold parallel lines, evading the key center, resisting attempts to be pinned down. There are pentatonic melodies and passages of striking bitonality.

The opening of Act II, which takes place at the restaurant Chez Bullier at night, is a crowd scene for a chorus of revelers that unmistakably recalls the Café Momus act from "La Bohème." Except that here the music has an ominous element, with minor-mode, wandering harmonies and fitful rhythmic energy. Even the waltzes and hints of tango that run through "La Rondine" are weighty, busy and harmonically thick.

The quartet of two young couples in Act II at Bullier, which turns into an extended ensemble with chorus, is top-drawer Puccini, a deftly written piece that combines soaring melodic lines with shifting harmonies.

Yet Puccini does not make a big deal of the musical complexities. In this he reminds me of Mozart or, for that matter, Stephen Sondheim, who sometimes during perky ensembles will keep the complex musical details below the surface, as if to say, "Don't concern yourself, this is my business, just sit back and enjoy the show."

The colorful sets by Ezio Frigerio contribute to this production's charm, even if they draw from a mixture of styles. Magda's salon has Art Deco square columns, furniture out of an Astaire-Rogers musical and wallpaper alive with intricate images that recall Klimt murals. The pavilion on the Riviera to which Magda, like the rondine, or swallow, of the opera's title, flees with Ruggero in Act III is a sunny room with aquamarine stained-glass walls and ceiling. You can practically smell the sea air.

Mr. Joël, slated to take over the Paris National Opera in the fall, is still recovering from a stroke he suffered this summer and did not come to New York to prepare this production. But Stephen Barlow, who staged it at the Royal Opera, has done excellent work with the Met's cast and the chorus.

The opera presents a comic counterpart to Magda and Ruggero in the young couple of Prunier, a sardonic poet who debunks romantic love, and Lisette, Magda's feisty maid. Though Lisette adores Prunier in her coquettish way, she rebels at his attempt to boost her social standing by turning her into an actress for the cabaret, which proves disastrous. The tenor Marius Brenciu, in his Met debut as Prunier, and the coloratura soprano Lisette Oropesa as, appropriately, Lisette offer sweet, lively and well-sung portrayals. The bass Samuel Ramey brings his stentorian and increasingly wobbly voice, as well as stolid authority, to the role of Rambaldo, Magda's keeper, who offers to reinstate her in his life, even after she flees with Ruggero.

In the end Magda who never reveals to Ruggero the truth of her former life, does go back to Rambaldo. Ruggero, who has written to his parents about Magda, receives a reply from his mother welcoming into the family a woman she believes to be virtuous. When Magda hears this, she tells Ruggero that she can be his lover but can never in good conscience marry him.

In this final scene of separation Puccini seems unsure of himself. A Viennese operetta composer would have written a duet of melancholic resignation: sad, yes, inevitable, perhaps, but no tragedy. Puccini can't help infusing the breakup of his characters with anguished outpourings that seem out of place and overdone.

Yet somehow, in this sensitive staging, thanks to the expressive performances of Ms. Gheorghiu and Mr. Alagna, this excess of Italianate emotion just makes "La Rondine" more appealing.

Late Puccini with star power

David Patrick Stearns, Philadelphia Inquirer, 3 January 2009

Best not to search for logic behind the Metropolitan Opera's opening of a new production on New Year's Eve, or why the opera in question was Puccini's little-known La Rondine, and why its notoriously temperamental stars,

Angela Gheorghiu and Roberto Alagna, are being such good sports about working over the holidays.

Just enjoy the total package as a handsome, amiable and sonorous rest cure from our tumultuous year. Though melodiousness is high, plot stakes are low. Daggers aren't drawn. Poison isn't ingested. What could be a tad boring in the opera house is likely to exude more up-close charm at the Jan. 10 high-def simulcast in Philadelphia-area movie theaters, when the star charisma, in this case, may well be more apparent to the camera.

The opera has always been a star vehicle at the Met, where it was once heard with Lucrezia Bori and Beniamino Gigli - two golden names - but not since 1936. More recently, velvet-voiced Anna Moffo was Rondine's patron saint thanks to her famous recording of the opera, followed by Kiri Te Kanawa and now Gheorghiu and Alagna, who not only made a lauded recording on EMI but also defied their respectively touchy reputations (she was fired from Lyric Opera of Chicago, he walked out on La Scala) by going so far as to perform it in concert outdoors in Brooklyn last year.

Attempted Rondine dramatizations are another matter - and not necessarily due to the usual lousy-libretto problem. This is later Puccini (1917), and like many great theater composers, he appeared to have lost interest in the storytelling elements of his art and simply wanted to compose. The plot about a Paris courtesan who loves and leaves an innocent young prospective husband is full of surprisingly familiar operatic situations. The spirited, outspoken maid goes out on the town wearing her mistresses' frocks like Adele in Die Fledermaus, everyone collides at an upscale version of Cafe Momus in La Boheme, and the end of the affair aches with the feminine nobility of La Traviata's Act II.

However, Rondine doesn't want to be those antecedents (at least not very badly), and doesn't sound like them. The popular idea that Puccini was out to be Franz Lehar isn't borne out by the score, which shows a restless composer scaling back on his usual lush orchestration and employing serpentine, almost Asian-sounding modes that are perfectly intriguing on their own terms but do nothing to illuminate characters or plot. Bursts of lyricism occur often enough in this relatively short opera. It's never less than pretty. Unlike Thaïs (the third-rate work of a second-rate composer), Rondine is the work of a great though muted genius.

Similarly, the Nicolas Joël production economically recycles scenic elements from act to act, sometimes at the expense of scenic specificity but never lacking art deco details and stopping short of overblown Zeffirelli-ism. Well, maybe not that short - the final act's south-of-France hotel porch resembles those massive greenhouses in Longwood Gardens.

The Gheorghiu/Alagna factor prompts no simple response. This real-life couple, sometimes called the Bonnie and Clyde of opera, have always been fine artists as well as stars. But due to its theater size, the Met hasn't always showed their midweight voices to best advantage (which is why their on-camera performances are more promising). But Gheorghiu's communicative concentration overrode that, even when the staging put her at further disadvantage. Alagna's tenor lacked warmth but felt healthier than in some recent seasons. Their stage chemistry is about ease. They know and anticipate each other's moves effortlessly. And boy, can they smooch - unlike most leading singers, who kiss as if one or the other needed Velamints.

They're mostly well matched by tenor Marius Brenciu and soprano Lisette Oropesa, though in the small but pivotal role of Rambaldo, the 66-year-old Sam Ramey nearly embarrassed himself with his declining vocal state. Marco Armiliato was the sympathetic conductor with a score that needs something more vital than sympathy.

La Rondine

Eric Myers, Variety, 5 January 2009

Not seen at the Met since 1936, Puccini's "La Rondine" makes a welcome return bolstered by the star power of its real-life husband-and-wife leads Angela Gheorghiu and Roberto Alagna. Nicolas Joel's well-traveled production -- it has already been seen in Toulouse, London, and San Francisco -- muddles the characters' motivation with an ill-considered change of era, but Puccini's genius, as usual, wins out.

The composer's attempt at a lighter opera, in which nobody suffers much more than a broken heart, did not become a repertory staple until New York City Opera revived it in 1984. That launched the neglected 1917 work on a love affair with audiences around the world, one which continues unabated.

The Met has lagged behind most other major international opera houses in presenting this crowd-pleaser. Brimming with several of Puccini's most seductive melodies, including the familiar "Chi il bel sogno di Doretta," "La Rondine" (The Swallow) is a work that carries more than a whiff of "La Traviata" in its plot.

Magda (Gheorhghiu), a sophisticated mid-19th century Parisian courtesan, flees a relationship with a wealthy older man and throws herself into a passionate romance with an ardent young admirer. She bravely ends this affair as well when she realizes the young man's family will never accept her due to her former status as a kept woman.

What works in the original Second Empire setting makes little sense in Joel's production (staged here by Stephen Barlow), which transposes the action to Puccini's later years. By that point in time, World War I and its societal upheavals had already ushered in the dawn of the Jazz Age, and millionaire scions of old-moneyed families were marrying chorus girls. Magda's tearful insistence to her lover that "I cannot enter your home...I was not pure when I came to you!" is mighty hard to accept in this updated context.

Nonetheless, the production is a visual feast. Franca Squarciapino's costumes are dazzling and true to the late-1910s concept -- except for the Vegas-showgirl-style slits that go all the way up the sides of Gheorghiu's Act I dress. Ezio Frigerio's opulent settings are stunning, though they are more representative of Viennese Secessionism and Louis Comfort Tiffany than anything that could be considered French.

The role of Magda is well-suited to Gheorghiu's earthily-tinged lyric soprano; she recorded it 13 years ago for EMI and has since made a specialty of it. Why then, does this ferociously stagewise performer seem so ill-at-ease in a production that is already familiar to her?

Her stances and gestures are uncharacteristically awkward and wooden. She is also beset with an unbecoming shoulder-length wig that is totally anachronistic; it looks like a castoff from Barbra Streisand impersonator Steven Brinberg. Fortunately these drawbacks do not impair Gheorghiu's vocal performance, which remains heartfelt and beautifully phrased.

Alagna is charming as her thwarted lover Ruggero; he should just remember that this is not "Tosca" -- he needs to float his climaxes rather than attack them. It's a pleasure to watch the very real onstage chemistry between these married superstars; during a long kissing sequence in the second act, they go at it like Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman in "Notorious."

Samuel Ramey represents luxury casting in the smallish role of Magda's sugar-daddy Rambaldo; he was ill the night of Jan. 3 and was capably replaced by James Courtney. Fast-rising soprano Lisette Oropesa is memorably comic and sings sweetly as Magda's maid and confidante. She is ably partnered by Romanian Marius Brenciu as the poet Prunier. Brenciu has a strongly-focused lyric tenor and boasts an appealing, naturally elegant stage presence. This role is his Met debut; we will surely be hearing more from him.

Marco Armiliato conducts the sparkling score with great verve, but he needs to hold his musicians down a bit. Far too often, the singers are smothered under the force of his orchestra. Opened Dec. 31, 2008. Reviewed Jan. 3, 2009