REVIEWS

I Pagliacci, Los Angeles Opera, September 2005

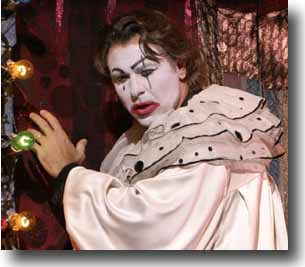

Photo of Roberto Alagna as Canio by Robert Millard

'Pagliacci' kills - literally and quite figuratively, too, Los Angeles Daily News, 14 September 2005

A full-throttle 'Pagliacci', The Orange County Register, 13 September 2005

Pagliacci, The Hollywood Reporter, 14 September 2005

Clowning Around, Opera Style, Los Angeles Downtown News, 19 September 2005

L.A. Opera's season kicks off with a wild 'Pagliacci', Los Angeles CityBeat, 15 September 2005

Slower and louder but just as opulent, Los Angeles Times, 13 September 2005

____________________________________________________________

'Pagliacci' kills - literally and quite figuratively, too

Los Angeles Daily News, 14 September 2005

Such is the combined star power of tenor Roberto Alagna and soprano Angela Gheorghiu that even Franco Zeffirelli's highly illuminated production of Ruggero Leoncavallo's "Pagliacci" cannot outshine them. Proof of that came Sunday afternoon, when the Los Angeles Opera revived the director's busy, modern-dress staging of this last word in circus blood lust.

Alagna and Gheorghiu, who are married in real life, are individually among the world's great singers. Together they are an operatic phenomenon: gifted singing actors whose uncommon physical attractiveness is exceeded only by their ability to electrify a stage.

So it was with real anticipation that opera lovers greeted the news two months ago that Alagna, replacing the previously announced Ben Heppner, would join his wife in this production, first mounted exactly nine years ago for Placido Domingo and not presented in Los Angeles since.

The role of Canio, the murderously jealous clown married to an unfaithful wife, does not leap to mind when one thinks of Alagna, whose voice is more naturally suited to less taxing, more lyrical parts. And the tenor's genial stage presence and gift for slapstick have secured his reputation in comic, rather than dramatic, material.

So his success here was by no means assured. Indeed, his snarling entrance signaled trouble, his voice sounding pinched, his vibrato irritatingly elongated. Yet his acting was uncompromised - his glare suggesting a dangerous possessive streak, his swagger a wife beater.

But not until the opera's most famous music, the anguished aria "Vesti la giubba," did Alagna come into his own. Freed from vocal constriction, he sang vigorously, pleasingly and movingly.

By contrast, Gheorghiu didn't need time to warm to her role. Her coquettish, rather than sultry Nedda was enchantingly voiced from her first notes, which, as always, glowed from within. In her portrayal, Nedda's infidelity - depicted on stage in lovemaking scenes with Silvio (virile baritone Mariusz Kwiecien) - seemed fueled by love rather than lust. And chillingly, her fear of Canio was visceral.

Baritone Alberto Mastromarino may strike some as too smarmy and unsympathetic for the role of Tonio, who introduces the opera and facilitates its tragic arc. But he sang warmly and expressively, and his enigmatic smirk at the opera's conclusion left a lasting impression.

Nicola Luisotti conducted the score with a conviction presumably only native Italians can muster. His ability to engage the orchestra to share his enthusiasm should be noted, for too often such music trudges when it should rage.

Zeffirelli's production, this time directed by his protege Marco Gandini, has been knocked for its extravagance - the action takes place under a highway overpass and in front of a meticulously detailed, dilapidated apartment building. But what could be truer to the verismo spirit of this opera than what Zeffirelli has wrought? And never has updating an opera been as smoothly accomplished as here.

Gandini proved an expert traffic cop, which in this production amounts to highest praise. And the final scene, in which Canio - presto-chango - turns from clowning to double homicide, had all the tension of a first-rate thriller, plus the added bonus of watching Alagna and Gheorghiu put the drama back in melodrama.

A full-throttle 'Pagliacci'

Timothy Mangan, The Orange County Register, 13 September 2005

"Pagliacci" sneaks up on you. It's made with as much savvy as inspiration, as if Leoncavallo were setting a trap for his audience. It begins, of course, with Tonio, a clown in a commedia dell'arte troupe in the opera, coming in front of the curtain and singing directly to us, revealing that the story we are about to see is taken from real life. This may be an old ploy, but it is effective here all the same opera rarely attempts to break the fourth wall.

The curtain goes up and we are dazzled in eye and ear: a crowd scene with the troupe arriving for its show, a musical and physical hubbub. Our senses stimulated, Leoncavallo then settles down to his story, told patiently, in detail and in real time, the break separating Act One from Act Two a mere "later that same day" span. There are recurring musical themes, tiny cells of material barely noticeable, that Leoncavallo plants in your subconscious.

Then there's the brilliant ploy in Act Two the play within the play that we watch as the audience on stage watches (there's even music within the music). Then, the reversal. Soon, it is a play no longer, but a murder scene, and Tonio sings (or Canio, depending on which version is done), "The comedy is finished." The overall effect is the opposite of making you more aware of the composer and his creation. It sucks you in.

The famous aria "Vesti la giubba" is like a microcosm of the overall plan. It is sung while Canio dons his clown costume and smears on the greasepaint. While our attention is thus engrossed, Leoncavallo is slowly building the music underneath, sneaking the vocal line ever higher until he springs it on us a melodic and harmonic scrap that he had planted in the Prologue, now sung full-throated by the tenor in beautiful anguish, the orchestra bursting. "Ridi, Pagliaccio," Canio sings, "Laugh, clown," at "your broken love," at "your pain," which he does, bawling at the same time. One is always surprised by the real power of this moment.

Los Angeles Opera's production of "Pagliacci," running through Oct. 1, pulls out the visual stops. This is a revival of the 1996 Franco Zeffirelli production and, Zeffirelli being Zeffirelli, the stage is crowded and busy and cinematically realistic and all about Zeffirelli. He has reset the action in a contemporary urban tenement, complete with ethnic gangs, sailors, prostitutes, motorcycles, cars, gelato stands, televisions twinkling in apartment windows and as far as we know probably toilet paper in the bathrooms, too. It's the kind of visual overload that Zeffirelli is often criticized for and that audiences literally applaud (as the crowd did Sunday). In this instance, the production felt as if it served Leoncavallo's naturalistic aesthetic well enough.

Roberto Alagna is the Canio in a disco shirt open to the sternum and plenty of jewelry, a machismo type to whom we are initially unsympathetic. He wins us over with a stirring "Vesti la giubba," though, and some pretty good acting. Alagna's tenor was in good shape, too, and it was a thrill to hear him jolt out those high notes.

His wife, Angela Gheorghiu, made an unusually lovely Nedda. The voice appears incapable of making anything but the smoothest, creamiest, most gorgeous sound, and she never pushes it either. Partially because of this, Gheorghiu's Nedda seems a bit too gentle and innocent, incapable of what she does, but this is an observation, not an objection.

There are genuine flaws to be discussed. Zeffirelli's stage for the commedia dell'arte troupe in Act Two is too small for them to properly move about. During the play, Alagna chooses to portray Canio as emotionally crushed and zombie-like, making his transition to outrage and murder something of a stretch. Quibbles. More seriously, L.A. Opera has chosen to insert an intermission between Act One and Act Two (probably in an effort to stretch out a short evening "Pagliacci" is only about 80 minutes long). The interval saps Leoncavallo's carefully built momentum.

Alberto Mastromarino embodies a hulking, vibrantly voiced Tonio. Mariusz Kwiecien makes a manly Silvio, his husky baritone occasionally straying into stridency. The reliable Greg Fedderly manages an ideally sympathetic Beppe even through all the makeup. The chorus sings robustly despite all its stage business. Zeffirelli's deputy, Marco Gandini, handles the human traffic jams capably.

In the pit, Nicola Luisotti brings out warm instrumental details, phrases with a measured lyricism, shadows his singers knowingly and never lets the intensity flag. What more could you ask for?

Pagliacci

Madeleine Shaner, The Hollywood Reporter, 14 September 2005

Ruggero Leoncavallo's short opera takes the extreme pleasure of love, and the supreme pain of betrayal, each with its matching arias of joy and desolation, and duplicates their journey through pleasure to the inevitable fires of hell. "Pagliacci" ("The Players") impacts the senses at a deep emotional level that only opera can pierce; there is no palliative for the residual scuffing of the heart that lingers long after those four final words of the drama -- "The comedy is over" -- are spoken.

The appeal of the piece is elemental. Within the play about the joyous arrival of a group of traveling players in a country village is another play that is taking place behind the commedia dell'arte masks of the players. Canio (Roberto Alagna), the prince of the players, doubles in the role of Pagliaccio in the masque. Nedda (Angela Gheorghiu), his put-upon wife, plays the put-upon Columbine. Tonio, a misshapen clown (Alberto Mastromarino), in love with Nedda, plays Taddeo, a misshapen clown in love with Columbine. Only Nedda's secret lover, Silvio (Marius Kwiecien), plays only himself, a terminally disastrous choice as it turns out. As lighthearted as the masque purports to be, ominous shadows lurk behind the ghastly whiteness of the commedia faces. (In an admittedly silly aside, the play within the play, which explores the dark side of love, is made even more poignant, at least for this romantic, by the fact that Alagna, who plays the cuckolded husband in both the opera and the masque, is married in real life to Gheorghiu, who plays the unfaithful wife.)

Do hearts really break? No one listening to Alagna's searing rendition of Canio's "Vesti la giubba," (the familiar "Laugh, clown, laugh"), or seeing him collapse in heart-deep sobbing when he realizes the truth of his situation, will ever quite forget the moment. Nor will Nedda's lament as she sings for her life fade quickly from sense memory. All the voices are superb, magnificently orchestrated and conducted by Nicola Luisotti and a splendidly tempered orchestra.

Producer and set designer Franco Zeffirelli has designed a quite magnificent three-tiered set representing the piled-up hovels of a poor village community, perfectly in place for the seething humanity of its denizens. A fireworks-sparked trailer rolls in with the traveling players and becomes part of the village scene that, in part, echoes the fraternistic chaos, beauty and ugliness of the raft of human and inhuman emotions that beset mankind at every level of society.

Stage director for this totally memorable production is Marco Gandini, who handily takes the chaos and makes it real. Great costuming by Raimonda Gaetani, lighting by Alan Burrett and the usual splendid support of concertmaster Stuart Canin and chorus master William Vendice make everything work.

Clowning Around, Opera Style

Marc Porter Zasada, Los Angeles Downtown News, 19 September 2005

Costumes Swirl, Voices Soar in Superb 'Pagliacci'

Even if you've seen Canio stab Nedda a dozen times on a dozen stages, you will be dazzled by the Pagliacci now playing at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. As part of its 20th anniversary season, Los Angeles Opera has revived the 1996 production by Franco Zeffirelli and has brought in the potent husband-wife team of Roberto Alagna and Angela Gheorghiu as the jealous clown and his cheating mate.

The clowns of Pagliacci don't always play nice: In addition to entertaining the masses, they carry out adulterous affairs and murder. Photo by Robert Millard.

Voices soar. Costumes swirl. Eurotrash mills the stage. Who could ask for more?

Pagliacci offers the purest tale of jealous Italians in an art form rife with jealous Italians; like a straight shot of Cinzano, it's short and bitter, with a sweet aftertaste. A traveling troupe of Commedia Dell'Arte players arrives in the public plaza of an Italian village, where they will perform a comedy about a jealous husband. But tragedy erupts as the head of the troupe discovers his leading lady has been unfaithful. Onstage at the performance, he demands to know the name of her lover, and when she refuses, he takes both her and her lover out, right in front of the crowd.

For his production, Zeffirelli re-created a vivid scrap of urban life in the manner of great Italian cinema: the façade of a bordello, a tiny bar and a public plaza dominated by a huge freeway overpass. The action seems to arise directly out of a heady mix of vendors, Vespas, aimless crowds, blue jeans, street dogs and street urchins. It's a setting that would have brought tears of joy to Ruggero Leoncavallo, the composer and librettist who gave Pagliacci life in 1892.

Actually, four Italians worked to deliver this perfect verismo: Zeffirelli is aided by stage director Marco Gandini, costume designer Raimonda Gaetani and energetic conductor Nicola Luisotti, who keeps the musical drama crisp and bold, despite extending the score a little longer than usual.

Gheorghiu plays against convention to offer a strong, even domineering Nedda - a good counterbalance to the swaggering Canio. Her voice, at once sweet and powerful, delivers wonderfully controlled pianissimos and sharp dramatic thrusts. She twines beautifully with baritone Mariusz Kwiecien, who plays her forbidden lover, Silvio. We wish their amorous rendezvous could go on forever.

World-renowned tenor Alagna, born in France of Sicilian parents, makes a handsome and passionate Canio. On opening night, he struck a perfect balance between masculine swagger and tragic jealousy, and his voice reached out to the rafters. The applause after his wrenching "Ridi, Pagliaccio" proved deafening.

Despite the tragedy, husband and wife obviously enjoyed the evening immensely.

Alberto Mastromarino made an appropriately menacing and grotesque Tonio, and despite some tiny vocal problems in Act 2, Greg Fedderly was an excellent and colorful Beppe. The chorus, under master William Vendice, was a marvel and a delight.

L.A. Opera's season kicks off with a tame 'Duchess' and a wild 'Pagliacci'

Donna Perlmutter, Los Angeles CityBeat, 15 September 2005

[...] The next afternoon brought a revival of Franco Zeffirelli's 1996 Pagliacci. What comes to mind seeing these two productions one after the other is that L.A. Opera just might think more is always better more supernumeraries, more frenetic stage-business, more spectacle, more explosions of confetti and glitter. In short, everyone loves a circus, right?

Well, Zeffirelli could argue his license here in Leoncavallo's La Strada-like drama of a poor little commedia dell'arte troupe traveling from one small Italian town to another, run by the jealous chief clown, who is married to the girl of everyone's dreams.

The street scene on which the curtain rises may not do much to focus the principals, or serve as a clue to the work's verismo with a vengeance. But it's a dazzler in its own over-the-top way. In front of a three-story tenement with occupants staring down from their balconies, a world of motley types mills about: hookers in leather shorts and thigh-high boots, toughs with mohawks, roller-bladers (natch), and a whole menagerie of sideshow sensationalists, including a tall black transvestite with a blonde wig. Where to look first? How to see it all in the allotted time?

When the stardust settles, there's Angela Gheorgiu, the Romanian soprano of everyone's dreams, as Nedda, the wayward wife-ward of the murderously raging Canio (her real-life husband, tenor Roberto Alagna). Together for the first time in an opera where she becomes his victim, they both bring compelling pathos to their portrayals. She, in an exquisitely calibrated duet with her lover Silvio (sung by sweet-voiced baritone Mariusz Kwiecien). He, in the famously tragic laugh-clown-laugh aria, "Vesti Ia Giubba," with all the sobs rendered to maximum effect and delicious, ringing tones everywhere.

Yes, we miss Plácido Domingo in the role. Nine years ago, he gave us a vocally stellar Canio, one riddled with sorrow through and through, a broken man. Alagna is young and proud, which makes the portrayal more difficult. But at least this time, unlike the original, Canio gets to utter the post-murder line: "La commedia è finita."

And this time, baritone Alberto Mastromarino sang the hunchbacked Tonio, playing him less for sympathy, more for villainy, but struggling with the high G in his Prologue, while Greg Fedderly again made a brightly inspired Beppe.

Key to the high performance level was conductor Nicola Luisotti, who coaxed transparent textures from the orchestra and enforced wonderfully flexible, fluid tempos that met every vocal need.

Don't miss this one

Slower and louder but just as opulent

Mark Swed, Los Angeles Times, 13 September 2005

"Ridi, Pagliaccio." Laugh, clown, laugh at the pain that poisons your heart.

When Roberto Alagna, as Canio, sang this famous line in a murderous rage Sunday afternoon to bring down the curtain on the first act of Los Angeles Opera's "Pagliacci," he had two choices. He could see if any cheap jokes were still lying around the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. There had been more than enough the night before in Garry Marshall's adaptation of Offenbach's "The Grand Duchess," which opened this 20th anniversary season. Or he could go ahead and do what the composer, Leoncavallo, required: Kill his wife.

He stuck to the script and killed Nedda. He killed, onstage, his wife in real life, Angela Gheorghiu. At the curtain call, she gave him a big kiss.

This cuckolded clown, sitting alone in his dressing room applying white-face over his tears, is one of opera's searing images. This is a tight tragic tale of love, lust and revenge within a touring commedia dell'arte company, usually told in a little more than an hour. These itinerant players, confused about the distinctions between comedy and tragedy and between stage and life, are lost to their emotions. We focus on them and watch them unravel. Their audience doesn't interest them or us.

Franco Zeffirelli's production, first given by L.A. Opera in 1996 and now re-created by Marco Gandini, takes a somewhat different tack. The crowd scenes are meant to interest us very much. They're grand. A teeming tenement somewhere in Italy contains a city's worth of what look like 1970s types. There is room for cars and motor scooters. Acrobats parade. Some in the crowd appear to have mistaken the circus for the disco.

It's a dazzling, riotous spectacle, meant to be a show all by itself. Go ahead, applaud the sets, even if it is a little peculiar that the Music Center, with "Dead End" at the Ahmanson, now has two ultra-lavish productions glamorizing tenement settings.

It takes strong performers to make an impression on such a stage, stronger than those L.A. Opera has assembled. But that hardly hinders the conductor, Nicola Luisotti. Perhaps the most impressive aspect of Sunday's performance was the physically imposing playing he got from the orchestra. He is of the school of conductors who believe the foundation of the orchestra is the bass instruments, and he coaxes from them deep, rich, expressive playing. He likes slow. Very, very slow. And he likes loud.

The orchestra sounded great, but what with these sets and this conductor, the less powerful singers, meaning everyone but Gheorghiu, didn't stand much of a chance. So ponderously slow was the prologue, in which the misshapen clown Tonio, who longs for Nedda, introduces the opera, that Luisotti came as close to strangling a baritone as possible without touching him. The lightish-voiced victim here was Alberto Mastromarino.

Alagna is a lightish tenor who looks good, in a rakish European way. He has a natural lyric bent. He didn't embarrass himself, but you constantly sensed how hard he was working to overcome natural limitations.

Gheorghiu does have the power along with an intimidating dramatic intensity. Vulnerability is not her strong suit. She demonstrated not so much fear of Canio as disdain. You had the feeling that, had she been paying a little more attention at the climax, she could have wrestled the knife from him with little problem.

She sang her little aria to the birds beautifully but heroically, not sensitively. Her duet with her lover Silvio, adequately sung by Mariusz Kwiecien, was ponderously slow, heavy, more labored than sexual.

When this production premiered, with Plácido Domingo as a commanding Canio, some complained that a 70-minute opera did not give them their money's worth. Well, ticket prices have gone up a lot since then, but attention spans have diminished, and Luisotti's tempos add a good dozen minutes. With intermission, you're at the theater for more than two hours. And there is a lot to look at. It's enough.

This page was last updated on: September 21, 2005