REVIEWS

Faust, New York Metropolitan Opera, April 2005

Metropolitan Opera Offering a New 'Faust', Associated Press, 22 April 2005

Levine Takes a New Look at Gounod's Warhorse, New York Times, 23 April 2005

Close your eyes and enjoy the music, New Jersey Star-Ledger, 23 April 2005

In this 'Faust,' the devil's in the details, Newsday, 25 April 2005

Faust - Metropolitan Opera, New York, Financial Times, April 27 2005

Pape, Alagna in the Met's musically brilliant "Faust", Classics Today, 28 April 2005

We Have a Faust!, The New York Sun, 25 April 2005

Tradition Reimagined Revives an Old Favorite, The New York Observer, 2 May 2005

_____________________________________________________

Metropolitan Opera Offering a New 'Faust'

Mike Silverman, Associated Press, 22 April 2005

Charles Gounod's "Faust," a work rich in beautiful melodies but seriously short on emotional depth, has gotten a new production at the Metropolitan Opera that fits it all too well.

There's much too much to occupy the eye in the Andrei Serban production that premiered Thursday night.

It may be that he aims to distract the audience from the fact that Gounod's trivialized version of Goethe's epic is hard to take seriously today. A bare plot outline goes something like this: Boy meets devil, devil helps him seduce girl, girl gets pregnant and goes mad, boy is dragged off to hell, girl repents and goes to heaven.

But if "Faust" has a chance of making an impact, it's through a restrained, uncluttered focus on the music. Instead, we get a barrage of visual effects, some stunning, some silly. (Serban was guilty of the same overkill last season in his production of another French opera, Berlioz's "Benvenuto Cellini.")

So, for example, the village square in Act II is a pleasing riot of color and activity but do we need can-can dancers? In Act III, instead of entering alone, the heroine Marguerite has to play catch with a group of villagers while she sings her wistful song about the King of Thule.

Mephistopheles wears a different Santo Loquasto costume in nearly every appearance including a flesh-toned suit complete with reptilian tail in the church scene that opens Act IV. This scene should be the most chilling in the opera, as the devil taunts the now-pregnant Marguerite and prevents her for praying to God for forgiveness; instead, the devil and the band of demons who accompany him jump around so much that the effect is more frenetic than frightening.

The one time Serban leaves well enough alone for an extended period is during the love duet that closes Act III, and here the perfumed charm of Gounod's music gets a chance to cast its seductive spell, both on Marguerite and on the audience.

If you're going to perform "Faust" at all these days you'd better get the best possible singers, and here at least the Met has done things right with a group of international all-stars.

Much anticipation surrounded the great German bass Rene Pape, singing Mephistopheles for the first time anywhere. He was vocally resplendent, as always, and exuded tons of charm, though not enough menace. If his performance wasn't quite the knockout punch that other basses like Nicolai Ghiaurov have been able to deliver in the role, blame the director and all those costumes.

As Marguerite, the Finnish soprano Soile Isokoski gave a lovely performance, using her sweet, slightly tremulous voice to convey feminine vulnerability and passion. The role of Faust should be a natural for the French-Sicilian tenor Roberto Alagna. But he sounded stressed at times and uncertain of pitch, though he came through with a ringing high note in his big aria. Siberian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky lent class to the small part of Marguerite's soldier brother, Valentin, and American mezzo Kristine Jepson brought spirit and sincerity to the trousers role of Siebel, who admires Marguerite from afar.

Music director James Levine, conducting "Faust" for the first time at the Met, treated the score as if it were a profound masterpiece instead of a faded relic.

"Faust" was the first opera ever performed at the Met when it opened in 1883 and for many years was heard there more frequently than any other work. It's only in the last 30 years that it has fallen somewhat out of favor. This new production isn't likely to reverse the tide.

Levine Takes a New Look at Gounod's Warhorse

Anthony Tommasini, New York Times, 23 April 2005

The list of major operas that James Levine has never conducted is not long. One, of all things, was Gounod's "Faust." But Thursday night Mr. Levine finally moved this enduringly popular work off his to-do list, conducting the premiere of the Metropolitan Opera's new production.

You can understand his hesitancy. Gounod's score has some great music, timeless melodies and ingenious dramatic strokes. But there are hokey bits, awkwardly comic scenes and a high quotient of sentimentality.

Stocked with an A-list cast, including the tenor Roberto Alagna as Faust, the soprano Soile Isokoski as Marguerite and the bass René Pape as Méphistophélès, Mr. Levine leads a revelatory musical performance. He brings out the dignity and eloquence of Gounod's score and shapes the abundant melodies with suppleness and grace. Clearly, he hears echoes of Wagner in the music's stretches of bold chromatic harmony and rhythmic spaciousness.

Alas, if only the production team, headed by the director Andrei Serban, had followed Mr. Levine's lead and taken a fresh look at this repertory staple. Instead, Mr. Serban and Santo Loquasto, who designed the sets and costumes, offer a "Faust" with no discernible staging concept and no consistent look, just a jumble of clichéd images, laughable symbolism and extraneous action. During Joseph Volpe's tenure as general manager, when it comes to the bread-and-butter operas, the Met wants patrons to get their money's worthy. Excess rules. When in doubt, throw more stuff at the audience.

In this "Faust" the excess seems evidence that the production team was floundering. The story's setting has been shifted, vaguely, from 16th-century Germany to 19th-century France, Gounod's time and place. The drab-looking opening scene reveals the aged and despairing Dr. Faust in his study, cluttered with globes, candles and stacks of books.

Things perk up when Mr. Pape appears in top hat and tails as Méphistophélès. But immediately the silliness begins. The Devil is followed by four slavish attendants, sort of subdevils with pointed ears who could be the brothers of Halle Berry's Catwoman.

Act II, which takes place in a fairground in the village square, is a garish and chaotic disaster. Throngs of boisterous students, carousing soldiers and their buxom girlfriends and a troupe of roving players and dancing bears all skip, prance, unfurl streamers and wave more French flags than you can count.

Mr. Pape shows up as the Devil in a silly-looking rendition of a festive princely regalia, with puffy breeches and red tights. These are Mr. Pape's first performances as Méphistophélès, and he already owns the role. His singing is robust, incisive and chilling. So why make him look ridiculous?

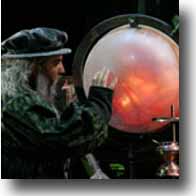

The worst for him comes later, during the terrifying scene in the village church, where the guilt-racked Marguerite, pregnant with Faust's child, goes to pray. Here Mr. Pape, wearing a rubberized bodysuit, appears as a naked Devil, complete with bulging muscles, exposed genitals and a serpent's tail.

Conjuring up something out of Hieronymus Bosch seems to be the idea. But when you have a singer who is really hunky, who exudes charisma and can convey danger with just a leering smile, why put him in a costume that elicits titters from the house? It's a relief when Mr. Pape appears in the final scene, looking utterly menacing in plain black pants and shirt.

You are grateful whenever you get a respite from the frantic activity. One fine moment comes in Act III, when Mr. Alagna, as the dashing Faust restored to youth, simply leans against the side of Marguerite's pretty house and sings the tender aria "Salut! Demeure Chaste et Pure."

Vocally, Mr. Alagna's performance of the role was uneven. He has a sure understanding of French style and an idiomatic way with the French language. His singing was ardent and lyrical. But his sound was sometimes leathery, and the way he scooped up to full-voiced high notes seemed a safety measure to reach the right pitch.

Ms. Isokoski, the admirable Finnish soprano, was a lovely and deeply affecting Marguerite. Hers is not a generically pretty and agile coloratura voice. There is a dusky quality to her tone. Still, she sings with great vulnerability and assured technical skill.

The role of Valentin, Marguerite's protective brother who goes off to battle, is not large, but the remarkable baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky made the most of every scene, singing with earthy sound and soaring lyricism. And, thankfully, the production team mostly left this handsome, white-maned, compelling artist alone.

The excellent mezzo-soprano Kristine Jepson was endearing as the young man Siebel, who has a crush on Marguerite. Jane Bunnell and Patrick Carfizzi were also fine in smaller roles.

But the production remains a major disappointment. Opera buffs should still attend, if only to hear the strong cast and marvel at Mr. Levine's work. And you don't want to miss Mr. Pape in the

Close your eyes and enjoy the music

Willa J. Conrad, New Jersey Star-Ledger, 23 April 2005

The Metropolitan Opera's new production of Gounod's "Faust," which opened Thursday, feels like a walk through a carnival funhouse. Any which way you look, the view is kaleidoscopic, distorted and surreal, without allowing the viewer much clue as to time or place.

Perhaps chaos is the concept of what was purported to be that most ironic of opera efforts, a "new" traditional setting.

Of all the production values of the Metropolitan Opera that could be parsed and dissected here, the one golden standard -- the company's quality of cast and musical values -- is the one unambiguous thing in this opera. James Levine conducted Thursday at the top of his game, easing the orchestra through a relaxed, romantic and effusive performance.

Tenor Roberto Alagna, in one of his signature roles as Faust, was in superb voice, spinning the role expertly with a warm, full and open tone. Baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky, with his creamy, rich tone and extraordinary musicality, could do no wrong as Valentin. Soprano Soile Isokoski, as the doomed Marguerite, had just the right mix of freshness and clarity in her singing, while mezzo-soprano Kristine Jepson cut an expertly balanced figure as the young boy Siebel, in love with Marguerite but unable to touch her. Mezzo-soprano Jane Bunnell, in the brief role of old lady Marthe, is a jewel.

This is also the German bass René Pape's first time singing the role of Méphistophéles at the Met, and in him, we have a fabulous proponent of the devil, a new generation of tall, hunky, athletic-looking bass with a flair for the smarmy and dramatic.

In short, go to this production to hear the singing, but ignore what you see.

Goethe's early 19th century "Faust," upon which the opera, written in the 1850s, was very loosely based, focused on a 16th century scholar, Dr. Faust, who sells his soul to the devil for the chance to be young and wretched by impregnating the naive and guileless Marguerite, thus defiling the thing he most revered.

Producer and director Andrei Serban seems to have decided to layer visual elements of all those eras together, moving the general locale to a 19th century French country village. Designer Santo Loquasto imaginatively and with much verve provides softly romantic costumes and contemporary sci-fi like images of the netherworld.

The stream of images -- soldiers in 19th century French uniforms, the devil in Renaissance tights and pantaloons (as well as full tux, a bizarre lizard suit and an officer's uniform), and Faust as both dusty Renaissance scientist, then Don Johnson-style, white-suited paramour -- is mindboggling. Serban and Loquasto are either very clever satirists, riffing with glee on the hoary history of costumes and sets of this most woolly of repertoire operas, or they are completely without discipline.

I choose the latter.

Unforgivably, as a director, Serban cannot decide whether the audience should expect to take things literally, as the appearance of Méphistophéles in a plume of smoke, or imaginatively, as the flowers that do not actually wilt in young Siebel's hands, though he sings an entire aria about it.

There's so much gorgeous singing, so many exquisitely shaped arias, so much commitment from this cast to the production, that the music carries the day. But, like its main character, this "Faust" is only falsely reborn.

In this 'Faust,' the devil's in the details

Justin Davidson, Newsday, 25 April 2005

In opera, embarrassment comes with the territory. Sooner or later, if you're a fine and dignified singer, you will find yourself trapped onstage in a situation or a costume so stupid that the voice of God couldn't save the scene. For René Pape, who has the body and bearing of a Hussar and who is probably the world's best basso, the moment came in Act IV of the Metropolitan Opera's new production of "Faust," the scene in which the illegitimately pregnant Marguerite enters a church to repent and finds a taunting Mephistopheles.

That would be Pape, cloaked at first in a monk's hood and cassock, which he sheds to reveal a hilariously muscled nude suit, armored in plastic pectorals and sporting gauzy wings, a prodigious codpiece and a 4-foot-long rat's tail. He looked less like Satan than like a third-tier superhero's nemesis. On the other hand, he was singing with Apollonian poise.

That was the nadir of a production by the hyper-interpretive director Andrei Serban that seemed intent on jolting a sluggish opera by sabotaging the music with stage business. The Met fielded a platinum-plated cast that marched through the evening with robotic perfection. Roberto Alagna sang Faust with engineered plaintiveness that never approached actual emotion.

Dmitri Hvorostovsky, who could sing the Moscow traffic code and make it sound ravishingly tragic, might as well have been doing just that. The electrifying Finnish soprano Soile Isokoski produced a precious "Jewel Song," but in the final acts seemed more puzzled than unhinged. Until the porno rat-suit episode, Pape acquitted himself best, bestriding the stage with Satanic majesty, wringing subtlety and fire out of a paper part.

There are, by my count, about 20 minutes of first-rate song in "Faust," which are what people come for and which the stars delivered with expected excellence. The rest of the nearly four-hour evening consists of intermissions (two of them) and stretches of pleasant reverie interrupted by bouts of tedium.

True opera fans accept this and consider the ratio of hit tune to dross worth their $170 per orchestra seat. But Serban wants more: Meaning! Depth! Social Commentary! So, for instance, he turns the triumphant-sounding scene of happy soldiers coming home into a funeral parade, oh so trenchantly highlighting the gulf between the jangle of militaristic optimism and the nasty reality of war.

As the moral universe darkens, Serban's pageantry becomes bolder. A Madonna statue bleeds. Marguerite's murdered baby is borne solemnly across the stage, impaled on a processional stake. Monsters out of "Where the Wild Things Are" press their horned and furry faces to Gothic church windows stained blood red.

Granted, Serban has grounds for these flourishes. Gounod's opera does gesture frantically in the direction of the parareligious kitsch. But it doesn't do the director any credit that he took that path with such tasteless zeal.

Faust - Metropolitan Opera, New York

Martin Bernheimer, Financial Times, April 27 2005

The Metropolitan Opera has always been sentimental about Faust. Gounod's essentially Gallic reduction of Goethe's ultra-Germanic drama served as the company's first vehicle, back in 1883 and the candy-coated opus has returned for its 714th performance in a new, heavily cut, bravely muddled production staged by Andrei Serban and designed by Santo Loquasto.

The management reportedly gave these two a mandate: Respect tradition. So they did, after a fashion. Tongues lodged loosely in cheek, they toyed, sometimes cleverly, sometimes clumsily, with the old romantic kitsch.

They imposed tragic symbolism here (lots of coffins), pretty-pretty images there (winged angels), portentous devices all round (supernumeraries fondling an hour-glass). With the action forwarded to the not-so-gay nineties, the kermesse became an overpopulated circus embellished with can-can girls. Marguerite's demeure chaste e pure was transported to Klingsor's garden in turn-of-the-century Bayreuth. Although hocus-pocus tricks were slighted, the final transfiguration conveyed fresh pathos, and character clichés were avoided. Dramatically this was a yes-but affair.

Musically, it was mostly yes. James Levine, who had never confronted Faust before, discovered uncommon sensitivity, even elegance, in the pit. He enforced propulsion where necessary, yet slowed for sentimental indulgence, mostly for his protagonist. Roberto Alagna's slender tenor tended to turn sharp under pressure, but his authentic diction and youthful ardour were compensation. The brilliance of the air des bijoux was muted, but Soile Isokoski's soft-grained soprano and simple demeanour proved affecting as Marguerite. Dmitri Hvorostovsky introduced a strikingly expansive Valentin. Kristine Jepson exuded sympathy as a gawky-boyish Siebel, and Jane Bunnell made much of the raunchy duties of Dame Marthe.

The evening was stolen, however, by René Pape,the powerful, playfully sardonic Méphistophélès. His basso, morecantante than profondo, rolled, roared and crooned, as needed, with easy insinuation. Strutting through the evil charades with a different costume from a different period in each scene, he underplayed the menace, and doubled its impact. This devil got his due.

Pape, Alagna in the Met's musically brilliant "Faust"

Robert Levine, Classics Today, 28 April 2005 [excerpt]

[...] Mr Pape's Mefistofeles is charming, smug and witty. And just about ideal. Almost on the same level is the Faust of Roberto Alagna. Mr Alagna can be an uneven singer; Tuesday night he was nothing of the sort. His phrasing was elegant, his French impeccable, his high notes rang out brilliantly and he delivered as much sweet, soft singing as he did powerful and heroic. His "Salut demeure" was gloriously sung. Bravo.[...]

We Have a Faust!

Jay Nordlinger, The New York Sun, 25 April 2005

"Habemus Papam!" rang the cry from Rome last week. ("We have a pope!") Well, I cry, "Habemus 'Faustus'!"We have a new "Faust" at the Metropolitan Opera, the sixth production in the company's history. (And remember, the Met began life, in 1883, with "Faust.") Directed by Andrei Serban, a Romanian-born professor at Columbia, it is rip-roaring, a killer. Boo-birds sang at Thursday night's debut, but when don't they? The Met has a production that will last, and please. Besides which, Gounod's opera was treated to a firstrate performance,on this opening night.

The entire production drips with sin, danger, torment, and illusion. At the end, of course, comes some light. The eye is almost continually appealed to, and amazed, and yet to my mind the production is not cluttered and distracting. We know the music, and the story: We can use some razzle-dazzle. Santo Loquasto's sets and costumes are imaginative and interesting, yet faithful faithful to Gounod and Goethe (not necessarily in that order).

Faust's study is gigantic, with a devilorange globe of some type in the centerleft (as we look at it).The people he senses, or dreams of, appear behind his foggy windows "Faust"is a psychological opera; Mr. Serban et al. bring off these elements very well. Méphistophélès makes a dashingly satanic entrance, in top hat and tails.Throughout the opera, he is assisted by weird biker beings. Among the touches in Act I are a "Rheingold"-esque rainbow and an ominous hourglass, telling us that time is cruelly limited.

Act II in the village square is a riot of color, and colorfulness. It swirls around like Gounod's music itself. There's a gorilla,striking King Kong poses also a bear and a kangaroo, and a Punch & Judy show, and hookers. What more could you want? Maybe flags, lots of flags more Tricolors than when France won the World Cup. Méphistophélès makes his appearance in the little box in which Punch & Judy have played.

Marguerite's home in Act III is indeed "chaste et pure," as Faust's aria has it. Her garden is improbably prolific, and a huge tree dominates the set. The church in Act IV is otherworldly and little consoling and who else but Death comes by with his scythe? Méphistophélès appears to be wearing some hideous marble body suit.Then,in Scene 2, that colorful village square has been jarringly stripped of life, and Death goes about his work.

Act V's prison is multi-tiered,skeletal, extraordinary I thought of a Japanese golf range with bars. (Perhaps you did not.) When salvation comes, the prisoners emerge slowly, wonderingly, like the rescued ones in "Fidelio." Marguerite is received by white-winged angels, while Faust is dealt a different,sadder reward.

Are some things a little hokey? Sure, but some things in "Faust" are a little hokey. Could I have done without the slow-motion sword fight between Faust and Valentin? Maybe but sword fights are always problematic, and everyone can do without something.To attempt to please everyone, in every particular, is a fool's errand.

In the title role was Roberto Alagna, who sang this same role at the Met two seasons ago. At the time, he had as his Marguerite his wife,Angela Gheorghiu, a singer as good as she is maligned, which is saying something. Mr. Alagna sang splendidly on that occasion, and less so on Thursday night. He had a rocky beginning, bleating, unable to find his pitch. Throughout the evening, he would be sharp, sometimes quite sharp. He did some forcing in this big house.But he was not unpersuasive,and he sings a beautiful French, does Mr. Alagna despite that name, he is a Paris kid.

The Met has had a tremendous parade of Méphistophélèses (how's that for a plural?): Chaliapin, Pinza, George London, Samuel Ramey, James Morris and now René Pape, the great German bass, enjoying his prime. When he sang "Le veau d'or," I thought, "King Mark [from "Tristan und Isolde"] as the devil!" But certainly by the time he reached his second aria, "Vous qui faites l'endormie," he was indisputably Méphistophélès.The voice is magnificent, of course, and the technique exemplary, but Mr. Pape also has the physical and temperamental tools for Méphistophélès: the bearing, the suavity...

Doing duty as Valentin was Dmitri Hvorostovsky, who looked super-smart in his gold-buttoned uniform. This was a rather Russian Valentin, but a good one. His aria, "Avant de quitter ces lieux," was smooth and affecting, with a gold-star A flat toward the end. As usual, this voice was a little contained, muffled one longs to pull it out a bit but it was elegant. Moreover, Valentin's death was admirably acted, unusually moving.

And who was Marguerite? The Finnish soprano Soile Isokoski, who scored a hit. Given Karita Mattila, this is a good era for Finnish sopranos. Ms. Isokoski offered a focused, darkish sound, and she sang with notable control. The Jewel Song was wonderfully feminine, even if its ending could have been giddier. In the love duet, Ms. Isokoski floated some beautiful high notes.And in the Act V trio,she was both cutting and lyrical remarkable.

There were several stars on the Met stage, but no one was better than Kristine Jepson, the mezzo singing Siébel. She has a superb, strong, vibrant instrument, and no end of accuracy. (At least that was the case on Thursday night.) "Faites-lui mes aveux" was eager, boyish, and totally winning. This is not always true of that aria.

Jane Bunnell did her job as Marthe, and Patrick Carfizzi did his as Wagner.

Important as the singers are, the key figure in "Faust" is the conductor, and this was the Met's music director, James Levine. He was conducting his first "Faust," believe it or not and he brought his usual intelligence, commitment, and musicality to what can be a silly and yawny score. His opening was virtually Wagnerian: measured, anticipatory,powerful.The best conductors elevate the lesser music. Act II's chorus was tight and rousing, and Act IV, Scene 2's was swaggering, with just the right amount of bombast suggesting the soldiers' false confidence.

The Met orchestra played well, and this was perhaps especially true of its woodwinds, which were even and assured. The Met's chorus also performed well,particularly in its hushed prayer on Valentin's death.

So, the Met has birthed a second smash production, new this season: Andrei Serban's "Faust," to go with Julie Taymor's "Magic Flute."The same criticisms may be leveled at each of them: too busy, too look-at-me. But I, for one, think they should be looked at.

Tradition Reimagined Revives an Old Favorite

Charles Michener, The New York Observer, 2 May 2005

The latest resurrection of Gounod's Faust at the Metropolitan Opera staged with compulsive vividness employs a cast that for uniform brilliance may surpass that of any Faust in the company's 122-year history. That's no mean feat: The opera has been performed at the Met more than 700 times; indeed, it inaugurated the old Met's house in 1883.

Gounod's retelling of the old fable about a 16th-century astrologer who makes a pact with the Devil eschews Goethe's revolutionary ruminations in favor of supernatural hocus-pocus, toy-soldier militarism, village frivolity and Christian treacle. A monument to French bourgeois sentimentality circa 1859 (when the opera was first performed), it presents a considerable challenge: how to honor the work's period charm while appealing to modern tastes.

Behind a weathered proscenium arch that might have been found in a Parisian flea market, director Andrei Serban and costume and set designer Santo Loquasto have given us a traditional Faust that every French schoolboy would love from the hero's tome-filled study, to the rose-strewn garden outside Marguerite's half-timbered house and the steely prison of her damnation. At the same time, they have reimagined Faust for a generation weaned on Andrew Lloyd Webber and Cameron Mackintosh. This Méphistophélès arrives with a retinue of prancing devilettes Cats with sequins. The village fair includes more hookers and cancan dancers (as well as a dancing gorilla and a dancing bear) than Toulouse-Lautrec would have known what to do with. The rejuvenated hero goes out into the world dressed all in white, as if for a Busby Berkeley musical. Marguerite's resurrection takes place in an ether inhabited by angels so saccharine you'd blush to find them on a Christmas card.

Mr. Serban, whose staging of Benvenuto Cellini last season set a new standard for clutter, reportedly had many more such "touches" in mind before they were blue-penciled by the Met's general manager, Joseph Volpe. I wish the pencil had been even heavier. Faust is a masterpiece of melodic beauty, textural variety (from the martial to the gossamer) and contrast between ardor and menace. It ranks among the sturdiest confections in French opera. With James Levine conducting his first performance of the work and showing an exquisite sense of its telling details and orchestral colors, this is, above all, a Faust for the ear.

On opening night, Roberto Alagna demonstrated that he has no rival today for sustaining the unaffected rapture essential to the French romantic tenor style (though he's showing an unfortunate tendency to approach high notes with an effortful "lift"). His Marguerite was the Finnish soprano Soile Isokoski, whose dark-hued vocal sheen gave unusual complexity to a heroine who can often seem a bewildered ninny. As her brother Valentin, the glamorous Russian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky brought down the house with his richly burnished "Avant de quitter ces lieux." The American mezzo-soprano Kristine Jepson sang the trouser role of Siébel with a splendid sincerity that belied the character's usual haplessness.

But in the end, Faust stands or falls on its Devil. René Pape, the towering German bass with the figure of a pole vaulter, the agility of a panther and a voice of thunder, isn't merely magnetic, he's all-enveloping. There was nothing insinuating or even sinister about his Méphistophélès there was simply implacable power. Disobedience was not an option when Mr. Pape was onstage. He and his colleagues in the cast (including the beautifully rehearsed choristers) have given the Met's oldest warhorse another lease on life.

This page was last updated on: May 7, 2005